Defining Gender

The first step toward understanding gender is to distinguish justified belief from opinion—the theory of knowledge is called epistemology.

Feminist epistemology examines the many ways in which gender shapes our worldviews, of what we think we know. Gender influences our knowledge of the world, and gender is itself a type of knowledge about the world, a way of relating to our surroundings. Understanding gender epistemology helps us understand how knowledge about gender is used as justification for subjugate certain groups of people.

Gender is embedded in time as well. Gender has a dimension of temporality, because gender as social practices—mannerism, comportment, sartorial choices, grooming habits, uses of voice—evolve over time and in different social spaces. Depending on time of day and on the social occasion, one may dress differently, for instance.

Gender practices are constituted, and sometimes undermined, by performative speech acts, by words that delineate ever-moving interpersonal relationships and social boundaries.

This chapter covers the fundamentals of gender studies as well as vocabulary. We will begin with contemporary views on main discursive features embedded within the notion of gender.

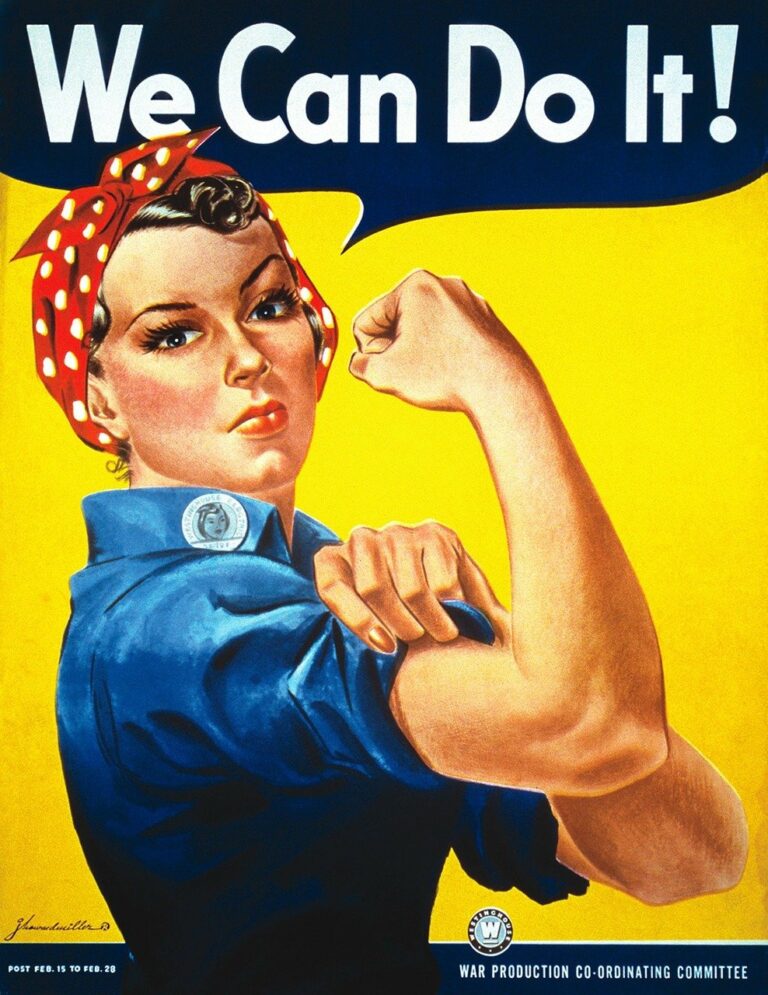

Gender theory is often associated with empowerment of communities. Let us explore this idea in contemporary screen culture, especially the presentation of so-called “strong” female characters.

The short video below examines “one of the most tiresome tropes” of superficially strong female characters. They are not women who are smart, capable, well written and complex, but rather bland, boring, and physically “strong” characters designed to pander to simplistic ideals of female empowerment.

What is your opinion on “strong” female characters in film? What defines strength? Is strength defined differently for different genders? What are the implications?

Feminism

- First Wave: 1848 – 1920

- Second Wave: 1963 – 1980s

- Third Wave: 1990s –

- Fourth Wave: Present Day (learn more by visiting the National Women’s History Museum)

Read more on the four waves of feminism as summarized by Sarah Pruitt for the History Channel.

Caveat: “The wave model has some virtues, but it also tends to overlook a great deal of heterogeneity of thought in any given moment” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

The first wave of feminism focused on gaining voting rights; the second wave fought for equality in education and the workplace. The third wave emphasized differences among women due to class, race, religion, etc.

Gender theories of the 1980s and 1990s in the US and UK made headway for gender equality, but they are, from our contemporary perspective, mainly forms of white feminism. They also did not take into account feminist thoughts in other cultures.

Scholars have updated and expanded upon these theories, bringing in, for example, the notion of intersectionality, critical race theory, and post-colonialism. Read more about intersectionality in Brittney Cooper’s chapter in The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory (2015).

Sex versus / and Gender

One way to understand gender today is through social constructs, but social upbringing and identity construction is not the full story. As Judith Butler writes in Who’s Afraid of Gender in 2024, “co-construction is a better way to understand the dynamic relation between the social and the biological on matters of sex.” Gender practices are co-constituted by individuals, their communities, and the society at large. Gender is a personal matter that is co-constructed in the public arena.

Butler reminds us that “although gender may be one of the apparatuses by which sex is established, it is important to understand racial and colonial legacies of the sex/gender distinction to chronicle the conditions under which idealized dimorphism emerged.”

Read the chapter on Race and Gender in Professor Joubin’s online textbook to learn more about how race and gender are co-constructed social notions.

Let us conclude this section with a quote from Judith Butler who wrote in 2024 that:

Rather than regard gender as the cultural or social version of biological sex, we should ask whether gender is operating as the framework that tends to establish the sexes within specific classificatory schemes. If so, gender is then already operative as the scheme of power within which sex assignment takes place.

When a designated official assigns a sex on the basis of observation, they rely on a mode of observation generally structured by the anticipation of the binary option: male or female. They do not answer the question “What gender?” Rather, they answer the question “ Which gender?”

The marking of sex is the first operation of gender, even though that obligatory binary option of “male” or “female” has prepared the scene.

In this sense, gender might be said to precede sex assignment, functioning as a structural anticipation of the binary that organizes observable facts and regulates the act of assignment itself (Butler, Who’s Afraid of Gender chapter 7 “What Gender Are You?”).

After reading this, how has your view on sex versus gender evolved? In what ways are they related or contrasting categories of thought? Let us think about sex assignment. When someone is born, they are assigned a sex. Social expectations follow which continue to assign gender to people. Notions of gender organize social life. Think of gender this way: people are inducted into a club unconsciously and sometimes involuntarily, so to speak. Society repeatedly applies the apparatus of categorization to assign these norms to embodied experiences.

Case Study # 1: Five Things about Gender

There are five things to know about gender. The most important characteristic about the notion of gender is that it is a type of social action. Gender is what we do.

First, gender is everywhere. As part of the core human experiences, gender has always structured our society and cultural activities, influencing what we do in our daily life, how we read history’s relevance to our times, and how we shape our collective future.

Second, knowledge about gender is often biased. Systemic discourses about gender often foreclose the possibilities of marginalized narratives to circulate or to even exist. The knowledge that is produced about gender is therefore complicit in the oppression of gender minorities. Such knowledge only benefits the socially dominant groups.

Third, we have a more accurate tool to examine gender. To more effectively capture the nature of gender, we can think of gender not as immutable identity categories but rather a set of social practices, such as grooming habits, sartorial choices, mannerism, and social spaces one may inhabit. Recent research even interprets genders as “porous and permeable spatial territories” that support “rapidly proliferating ecologies of embodied difference.” In other words, gender is connected to the social environments rather than simply one’s body.

Fourth, gender has social dimensions. The communal aspect of gender supports my theory that gender is a set of conventions and social practices. These practices evolve over time, in the presence of other people, and in different social spaces. With this in mind, we can analyze the what, how, and why of the communal connections around gender. I call this the sociality of gender. With this new tool, we can deconstruct the toxic formulations of the who of the identity categories. Those formulations rely on imagined membership of genders. The formulations are informed by problematic assumptions about the definition of, for example, women or who qualifies to be a member of a certain gendered group.

Last, but not least, gender is produced at the intersection of other identity categories such as race, class, and religion. Similar to other categories of identity, racial difference is often imagined as an inversion of what are perceived to be gender norms. Gender difference is often racialized, as well.

In summary, in this chapter, we have learned about key concepts such as:

- The pervasiveness gender in shaping our society

- Knowledge about gender is often biased

- Gender is not a category but a set of evolving social practices evolving

- The sociality of gender

- Gender intersects with racial, class, and cultural differences

Case Study # 2: Barbie

How does screen culture engage with notions of gender? One of the tools at filmmakers’ disposal is parody. Greta Gerwig’s Barbie (2023) satirizes both the goofy and equestrian patriarchy of the human world and the matriarchy of Barbieland by alluding to several films and by flipping well-known tropes without launching into explicit expositions of feminism.

For example, Barbie’s opening sequence, with voice-over narration by Helen Mirren, depicts how Barbie rescues girls from prehistoric ideologies. The scene pays homage to, and features the same musical soundtrack and the same sunrise as, Stanley Kubrick’s science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Watch the following short video which sets Barbie side by side with 2001: A Space Odyssey.

As shown by the side-by-side comparison in the video

- In 2001: A Space Odyssey, a group of hominins smash bones to create new tools. The appearance of a mysterious, futuristic black monolith speeds up the evolution as the sun rises over the horizon. Accompanying the epic scene of evolution is Richard Strauss’s “Sunrise,” the opening fanfare of his 1896 symphonic poem Also sprach Zarathustra (learn more about the music in the Gramaphone Newsletter).

In Barbie, a group of girls are playing with nondescript baby dolls. Suddenly, a supersized Barbie (based on the original 1959 doll) appears on the scene wearing a black and white striped swimsuit. Little girls used to play with baby dolls to rehearse motherhood. After Barbie appears, little girls smash the baby dolls in favor of diversified roles for women that range from the astronaut and surgeon to the CEO. The girls’ awakening is accompanied by the rising sun over the horizon.

Your Turn

In summary, in this chapter, we have learned about key concepts such as:

- The pervasiveness gender in shaping our society

- Knowledge about gender is often biased

- Gender is not a category but a set of evolving social practices evolving

- The sociality of gender

- Gender intersects with racial, class, and cultural differences

Let us apply these insights from gender theory to analysis of the film Barbie. Some of the prominent film techniques have important implications on gender dynamics and perception:

- Point-of-View (POV) shots may turn a female character into a sexualized object through the leery eyes of an observer or the camera-eye.

- Framing techniques that fragment female body parts singles them out for consumption disconnect the characters from their environment.

- Such camera movements as slow motion and tilt disassociate characters from real time in the narrative. These techniques make the characters more sensual and take away their control of the space they inhabit. Slow pan or slow tilt also prolongs the amount of the time.

- Lighting can flatten female characters’ features, making them attractive but less three-dimensional.

- A combination of these and other techniques, such as a fuzzy focus and an extreme close-up with no discernible background position the characters outside the narrative time and space. Due to the ways in which audiences are invited to view them, these sexualized characters become “inconsequential” to the story. When characters are disconnected from their environments, they are disempowered. They are not able to influence their surroundings and appear more abstract and less of a real person.

In what sense might we say Barbie undoes or replicates the dominant notions of gender (applying Judith Butler’s theory)? In what ways do the films un-do socially imposed gender roles of the male characters, masculine filmmaking perspectives (even when the filmmaker is a woman), and male audiences?

Watch the following clip. Stereotypical Barbie visits the so-called Weird Barbie to seek advice. Stereotypical Barbie believes she is malfunctioning: bad breath, flat feet, and cellulite on her thigh. Weird Barbie lives on the outskirts of Barbie Land.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of naming the “outsider” character Weird Barbie? What does this move deconstruct or affirm, and how?

Consider the film set, as well, which contributes to characterization. The set constitutes the cinematic space inhabited by the characters. How does the setup and decor of Weird Barbie’s house differ from those of Barbie’s house?

Bonus

For your amusement, check out this fan video in response to Gloria’s monologue in Barbie, “It is literally impossible to be a woman.” It is a video juxtaposing Washington Post’s Kate Cohen‘s politically poignant speech with the original monologue by Gloria (played by America Ferrara).

Further Reading

Some of the readings are open access; others may require George Washington University credentials.

Butler, Judith. “Why Is the Idea of ‘Gender’ Provoking Backlash the World Over?” The Guardian, 23 Oct. 2021

Butler, Judith. Who’s Afraid of Gender. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024