AI, Art, and Writing

How will human creativity evolve at a time when generative AI claims to be creating art and new pieces of writing on the fly? How do we build trust by keeping ethical human decisions in the loop? Art and writing remain central to our society, because we continue to have a great deal of synchronous and asynchronous interaction with information that consists of words and graphics.

With the emergence of easy-to-access generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, we now live in a world of unstructured information abundance. We do produce and encounter many types of writing, most of them in day-to-day context that seems mundane (T&C language; transactional, advertisement, product description, product review). Real estate agents do a lot of formulaic writing based on templates (descriptions of properties for sale).

However, other types of writing would not benefit from automation (machine learning). Writing is not merely a means to express one’s thoughts; writing is in fact part of the thought formation process itself. We refine our ideas through writing. And writing is a craft. Therefore, the technicity of art is as important as artistic foundations of technologies.

Google vs ChatGPT

The first step towards enhancing critical writing in the era of AI is understanding the crucial differences between how the Google search engine and large-language-model chatbots work. This knowledge will inform how we write and how we formulate queries.

- Google is an indexing portal that sends users on their way in various directions. It is not a content provider, though it has its own algorithmic biases as shown in search result ranking; there are also paid advertisements (see Google’s statement).

- In contrast, generative AI is a type of content aggregator that entices users to linger and chat more. Operating on tokens, it is a self-contained re-mixing machine of words and images (see OpenAI’s statement).

Since users do not expect Google’s outputs to be discursive (before Google infused AI Overviews), they do not tend to type out full sentences. Efficient queries on Google often consist of keywords combined with Boolean operators and avoiding stop words which are ignored by many databases. If we include stop words, the database may return far too many results.

High-quality prompts and queries for generative AI typically consist of full sentences and indicate explicitly the context as well as the desired tone and format of the output. The more detailed and context-driven a prompt is, the better the output will be.

While Google retrieves and ranks results based on keywords and term frequency (within queries and within web sources), generative AI draws on the prompts for contextual cues and generate results via tokens. AI’s outputs are a form of auto-completion and expansion of the queries.

Prompt engineering may sound like a new concept after the emergence of ChatGPT, but prompting a source or an interviewee is an important part of journalists’ job. Ill-framed questions or inappropriate prompts may not elicit desirable or quotable soundbites. Similarly, research begins with well-crafted, open-ended research questions that are capacious and thought provoking yet focused enough to be feasible as a project. Even with search engines such as Google, users can retrieve more accurate and useful results if they have thought carefully about keywords and parameters they are using. All of these prompting activities can be said to involve various levels of “engineering.”

Caveats: AI’s conversational interface generates texts that simulate fluent, human speeches. While search queries on Google lead to a hierarchical, but open-ended, list of links and sources, similar queries prompt the generative AI to produce full passages that give the impression of a lecture or essay, sometimes with first-person pronouns, which can be mistaken as the only and ultimate answer to the question. The self-contained output gives the false impression of singularity and neutrality. A solution to this challenge is to promote metacognition and critical AI literacy.

Art and Technicity

What are the relationships between algorithmic technology and art, especially the craft of writing? Here is Professor Alexa Alice Joubin’s talk at the World Bank on AI, Art, and Technology.

Are technologies an extension of humanity or a surrogate of it? Why do sentient robots often want to become “real” humans in movies?

Art is front and center in digital transformations of our society today, because art fosters creativity, and creative thinking leads to social change. Technology has always been intertwined with art, and artistic imagination has led to new tech designs. Art has also been used as proof of concept to launch emerging technologies.

When ChatGPT was launched in late 2022, the general public was transfixed by its ability to write poetry rather than its potential of carrying out bureaucratic tasks.

So, how do we use technology and art to make the world a better place? Art gives cultural meanings to technologies. In fact, every technology tells a story. It needs a description, and descriptions are essentially narratives.

Epistemic Justice

How do we write in an era of AI? How does generative AI (as a text-generating mechanism) impact our society’s relationship to written words and the future of the craft of writing?

First, it is useful to keep in mind that AI’s outputs amount to a blurry snapshot of the world wide web. Ted Chiang suggests that ChatGPT is “a blurry jpeg of all the text on the Web. It retains much of the information on the Web, in the same way that a jpeg retains much of the information of a higher-resolution image, but, if you’re looking for an exact sequence of bits, you won’t find it; all you will ever get is an approximation” (The New Yorker, 2023). The keyword here is approximation.

Secondly, we need to understand AI’s outputs in the context of epistemic justice. In many ways, the arrival of generative AI, with its celebrations and damnations, is an old story. Technological transformations have brought cyclical adulation with worry since at least the printing press. In The Gutenberg Parenthesis: The Gutenberg Parenthesis (2023), Jeff Jarvis characterizes the age of print, an era of Gutenberg, as a worldview about permanence and authority of the printed word. Jarvis noted that the emergence of the printing press was as disruptive as digital transformations today. Further, in The Science of Reading (2023), Adrian Johns reveals that reading is both a social affordance and an enterprise enabled by technologies of representation—the written or printed words.

Another part of AI and ethics, as well as epistemic justice, is pedagogy. Since the public release of ChatGPT, there has been a lot of focus among educators and students on the problem of cheating (academic dishonesty, see this article in Inside Higher Ed). Unlike traditional forms of plagiarism, generative AI’s output is more opaque. It does not outright copy a source verbatim. It regurgitates information in its datasets. Further, AI detection software has high error rates and can lead instructors to falsely accuse students of misconduct (Edwards, 2023; Fowler, 2023). Even OpenAI, known for their ChatGPT, discontinued their own software to detect AI-generated texts due to “low rate of accuracy.”

Similar to other types of distrust in educational contexts, the anxieties induced by AI’s presence reflect similar patterns for potential discrimination. Certain types of students may appear more likely to “cheat” using AI or other tools due to their race, gender, linguistic ability, and/or class background.

AI also has a linguistic diversity problem, unduly promoting normative white middle-upper-class English as the ultimate and only standard.

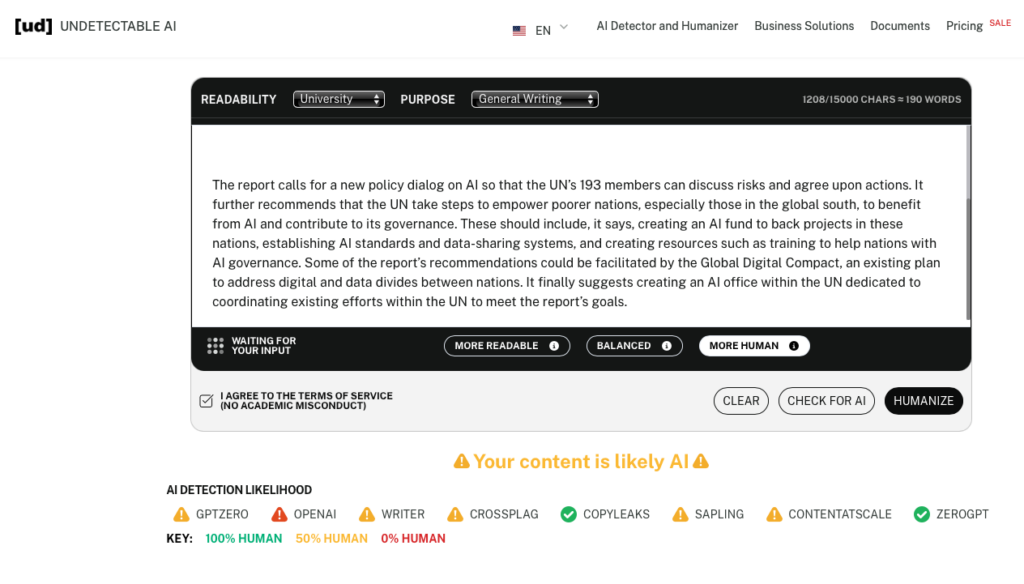

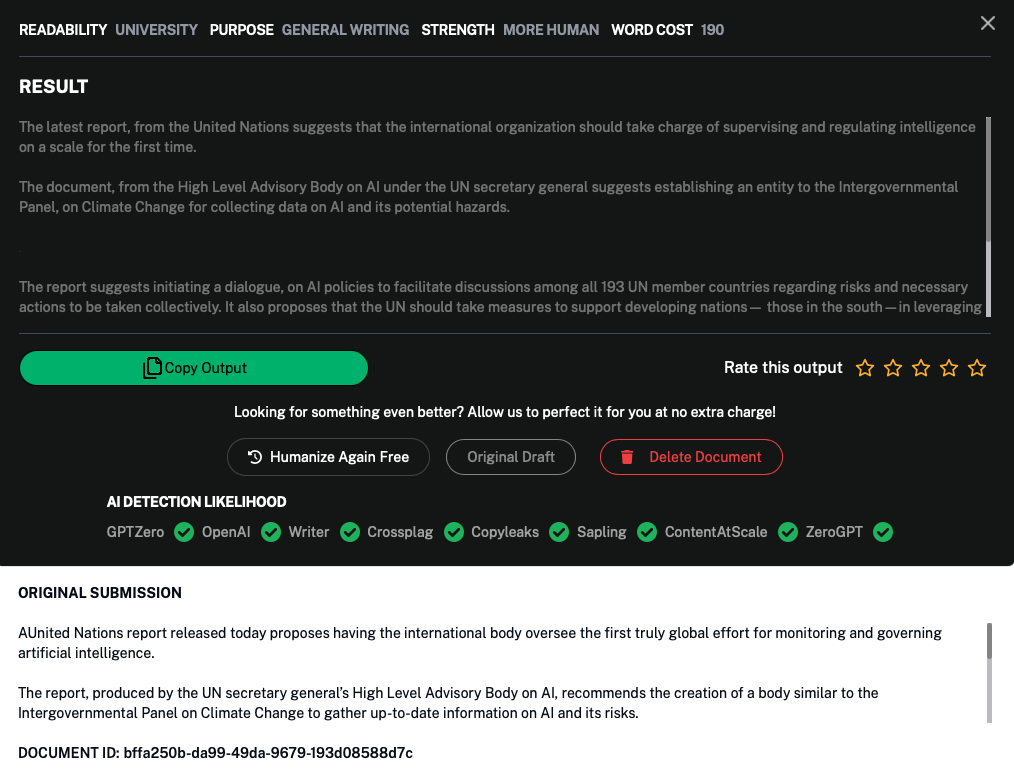

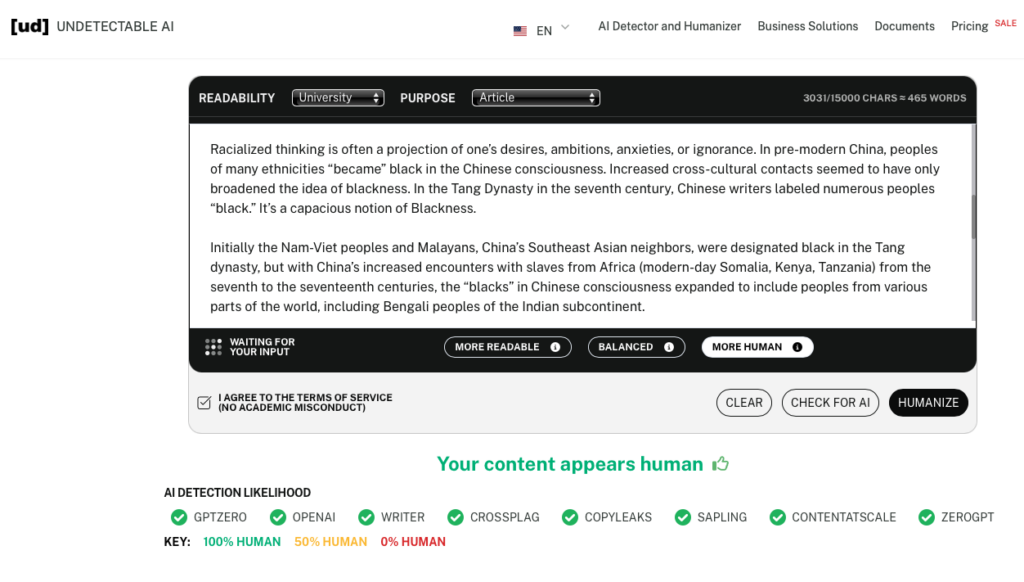

Adding to the already murky water are paraphrasing tools and software that claim to be able to “humanize” AI-generated texts, such as Undetectable AI. As shown by screenshots below, this tool uses AI, ironically, to rewrite texts and claim they can make the texts seem more human. Preliminary tests show that the so-called humanizing paraphrasing process merely adds grammatical or typographical errors and punctuation issues, degrading the quality of the prose.

It is more productive to think of writing in the era of AI as social collaboration. Quality is far more important than quantity, and rhetorical situations and effect are more urgent questions than provenance (origins of words) and tools involved in the creation of the texts (reference works, human or AI translators, Grammarly, etc.).

AI as / and Social Collaboration

We can think more critically about writing as a collaborative enterprise and as an activity enabled by techné–technical affordances (even pens are a type of technology). Techné governs all forms of synchronous and asynchronous representational technologies from the codex book to stage performance. Writing connects the technicity of humanity and emerging models of distributed and artificial intelligence.

Even AI models are themselves a collaborative enterprise in terms of their design and retrieval processes as well as the nature of the technology. AI is a type of distributive intelligence, the process of separating the function in a large system into multiple subsystems. It is labor intensive to clean and curate datasets and to de-bug and train AI models. When in operation, many models split the processing workload across various units and even across multiple locations. In cognitive psychology, distributed intelligence refers to the distribution of expertise across many individuals and situations. Intelligence is socially diffused and assembled.

AI models collaborate with one another to produce better results, as well, as evidenced by a MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory project called co-LLM. Their new new algorithm pairs a general-purpose base LLM with a more specialized model. “As the former crafts an answer, Co-LLM reviews each word (or token) within its response to see where it can call upon a more accurate answer from the expert model. This process leads to more accurate replies to things like medical prompts and math and reasoning problems” (see press release; you may also be interested in reading the paper on “Learning to Decode Collaboratively with Multiple Language Models”).

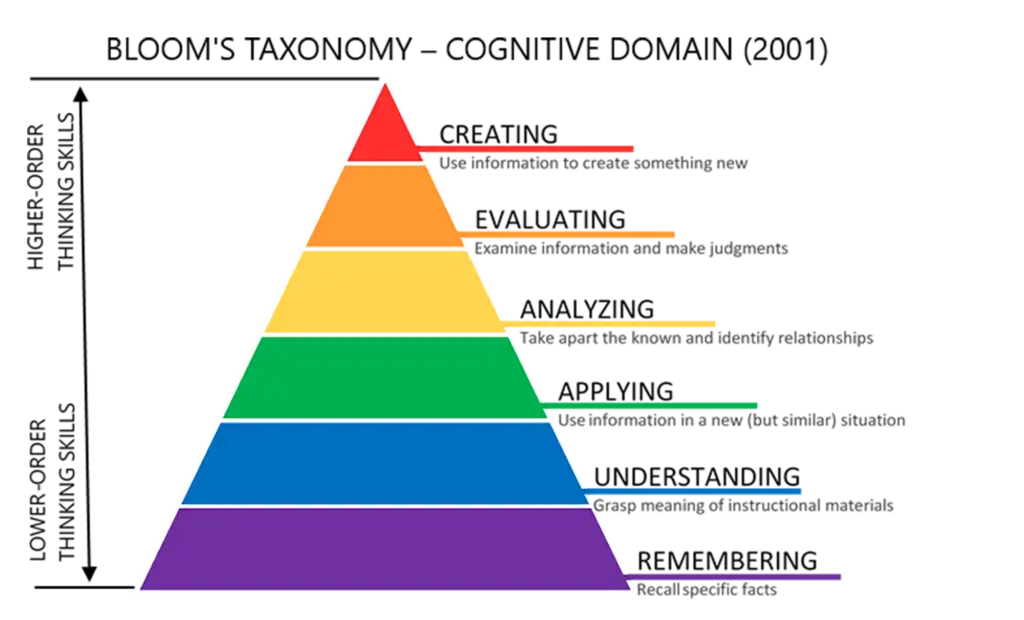

With this in mind, let us think the different levels of sophistication of prompts (queries) and what they may generative via AI models. One useful way to do this is to draw upon an updated model of the Bloom’s taxonomy. In 1956, Benjamin Bloom published a list of educational goals known as the Taxonomy of Educational Objectives which describes the 6 cognitive processes of developing mastery of a subject.

Writing in the Era of AI

We live in an inquiry-driven search culture. Algorithm-governed inquiries and responses frame our contemporary life. Many activities are affected, ranging from navigation to scholarly research. As Susanna Sacks and Sarah Brouillette write in “Reading with Algorithms“:

The processes that now structure daily interactions online are cultivated by more-than-human gatekeepers, which apply explicit and implicit logic established by human programmers to determine what kind and whose cultural productions are promoted.

Understanding the operation of AI helps us become more effective writers. Since generative AI produces outputs that are based on prompts, it is a form of auto completion that builds upon and extends the prompts. The quality of AI output, therefore, correlates highly with the quality of the human-initiated query with contextual details.

Moving forward in this inquiry-driven search culture, higher-level critical questioning skills are more valuable than basic skills of fact retrieval. Tasks such as pattern recognition and summarization of info are increasingly given to machines.

First, we need to identify appropriate AI tools for appropriate tasks. Do not use a hammer on every job. Second, we need the appropriate key, the prompt, to fully utilize the AI tool.

Finding the best tool is only the beginning. Next, we need prompts to unlock the power of AI. The key to operating these tools are high-quality prompts that are mission specific and have been field tested.

What is the current generative AI good for and good at? It is not advisable to rely on AI for cognitive tasks, but AI could be suitable for certain non-cognitive tasks. Cognitive tasks require a person to process new information and apply it on new cases. In contrast, non-cognitive tasks may involve routine and formulaic types of writing or pattern recognition.

The Modern Language Association (MLA) regards “ethical and effective use of generative AI technologies” as “an essential skill” today. Here are some highlights of the MLA’s definition of AI literacy:

- You have a basic understanding of how generative AI technologies work.

- You evaluate the relevance, usefulness, and accuracy of generative AI outputs. (You select strategies appropriate to the context, purpose, and audience for a task. ::: You can analyze generative AI outputs to determine whether the results align with the purpose of a task.)

- You monitor your own learning as you use generative AI tools. (You understand and can articulate why you used generative AI in a writing, reading, or research task. ::: You can explain how using a generative AI tool for writing contributed to your work.)

- You recognize that generative AI is fundamentally different from human communication. (You can evaluate whether the output from a prompt used as part of your writing process might result in miscommunication.)

- You understand the potential harms of generative AI, both those inherent to the technology and those that arise from misuse.

— Read more in Student Guide to AI Literacy

AI is not a reliable tool for cognitive tasks, but it can be used in drama education. When accuracy is not at stake, AI could become useful. For instance, through elaborate prompts and setup, we can have AI do role-playing with humans to test out various dramatic situations or even social scenarios.

A team at MIT designed “AI Comes Out of the Closet,” a large language model-based online system, to help LGBTQ advocates. The system leverages artificial intelligence-generated dialog and virtual characters to simulate complex social interaction simulations. “These simulations allow users to experiment with and refine their approach to LGBTQIA+ advocacy in a safe and controlled environment.” This is an innovative use of AI as a laboratory for humanity.

Further, in early stages of writing, it can be used as a form of social robotics or for social simulation. We could test the drafts of our writing by conversing with carefully calibrated AI (through elaborate prompting) to have it serve as a sounding board to gauge possible reactions to what we write. We can treat AI as a social surveillance instrument, since its output represents the means of common beliefs and biases within a society.

Current AI technologies are designed to accomplish limited and context-specific discursive and simulative tasks. ChatGPT is an aesthetic instrument rather than an epistemological tool.

Generative AI is not reliable or trustworthy in new knowledge creation, but its power can be harnessed to simulate social situations, to trigger human creativity in the arts, and to regurgitate information from datasets it trained on.

The randomness of large language models can inspire human creativity by suggesting less frequently trodden paths or uncommon association among objects and words. Some artists have taken advantage of and amplified AI’s randomness as an asset. Mark Amerika uses a predecessor of the current ChatGPT as a co-writing buddy to add layers of “creative incoherence” to his works (Amerika 2022). He uses AI to “defamiliarize language for aesthetic effect” and to increase his work’s “glitch potential,” a process which he compares to the common jazz practice of “intuitively missing a note to switch up the way an ensuing set of phrases get rendered” ( Amerika 2022: 5). One might say Amerika is performing opposite the generative AI in an improvised concert.

AI Helping Researchers

If used appropriately with care, AI can help enhance digital justice. One conundrum in researching and writing about historically marginalized voices is the invasion of privacy. Diaries or personal letters often contain sensitive information. How do we respect people’s privacy while making their erased history known? How do researchers make archival material available to the public without infringing on the privacy of historical figures?

AI excels in two types of tasks: pattern recognition and pattern reproduction. AI can anonymize sensitive data while preserving the usefulness of said data. AI could also recognize common patterns in handwriting to help historians answer questions of provenance.

AI has helped some scholars open up archives “while ensuring privacy concerns are respected,” such as the project “The Personal Writes the Political: Rendering Black Lives Legible Through the Application of Machine Learning to Anti-Apartheid Solidarity Letters.” Funded by the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS), the research team uses “machine learning models to identify relationships, recognize handwriting, and redact sensitive information from about 700 letters written by family members of imprisoned anti-apartheid activists” (see their interview here).

Your Turn: Comparative Counter Arguments

We will be doing two exercises.

- First, evaluate the sophistication level and effectiveness of your prompts for AI. Write a long prompt to ask AI to come up with counter-arguments to your thesis. Explain the context in detail.

- Second, try to come up with your own counter-arguments. Then, conduct a comparative critical analysis of AI’s textual outputs with your own writing to fact-check, detect unconscious bias (whether human or algorithmic), and assess quality differences.

In research writing, there are six levels of sophistication, as shown by the Bloom’s taxonomy below.

The illustration of the updated Bloom’s taxonomy shows a pyramid of six levels. The bottom, in purple, is the most rudimentary level of learning. It involves memorization of facts. Immediately above it, colored in blue, involves understanding the instructional material. The next (green) level involves successful application of the theory to new situations. The next (yellow) level leads to critical analysis of component parts of the subject. The next (orange) level involves critical evaluation of the information. The final, highest (red) level is the creation of new knowledge based on what one has learned.

As you create prompts to generate responses from AI, challenge yourself to move through the 6 stages of sophistication as you become more familiar with the subject.

Stage 1: Memorization of facts. Prompts at this level focus on retrieving facts and fundamental concepts.

Stage 2. Comprehension. This type of prompts lead to summarization of the reading and explanation of basic ideas.

Stage 3. Application. To devise prompts of this level, use what you have learned on new case studies.

Stage 4: Analysis. Level-4 prompts exhibit a fuller understanding of the concepts and provide examples to AI so that it can emulate you in dissecting the reading in terms of its structure and underlying patterns.

Stage 5: Synthesis. Create prompts to help you make informed judgments, such as assessing the quality and relevance of information.

Stage 6. New Knowledge Creation. This is the pinnacle of Bloom’s taxonomy. Pull together all the facts, concepts, information, and case studies to form a new perspective, propose a new theory, or create new knowledge.

Your Turn: Pattern Detection

Now, use the proprietary AI Teaching Assistant attached to this website to make your writing more effective and impactful. We should amplify AI’s strongest suit: pattern detection. Do not ask AI to write for you or to rewrite your prose. Ask it to help you detect patterns in your writing to enhance your personalized learning.

Here is a sample prompt:

Play the role of a writing tutor to help me enhance the precision of my writing. This is for a university course on critical theory. I need your help to detect repeated patterns in my writing and list them as bullet points. I want to know if I use certain words or certain phrases repeatedly or repeat certain statements. I also need to write with more concrete details and avoid general statements. Restating an idea without developing it does not make it a strong argument. The context is that I am analyzing a scene from the film _____. Please look into the screenplay and point out how I can make my observation of the scene more concrete and compelling. Here is my draft:

The AI here has been trained on the screenplays of the films we discuss in class, the assigned readings, and transcripts of the professor’s lectures. Therefore, it is a trustworthy tool compared to general-purpose AI chatbots.

To become better writers, we first need to become aware of patterns in our own writing. Some words that are used repeatedly by students (often unconsciously) include “clearly” or “throughout history.”

Here is the AI’s response to the prompt above (and a sample student essay in Hidden Figures). It provides feedback on patterns:

To enhance the precision of your writing on the scene, I have analyzed your draft and the screenplay. Below are observations regarding repeated patterns, specific word usage, and suggestions for incorporating concrete details.

Repeated Patterns & Word Usage

- Repetition of Terms: The phrases “race and gender” and “intersectional” appear frequently but without definition.

- Consider varying your language. The term “teacher” could be replaced with the character’s name to increase specificity.

- Precision: Phrases like “All the students, already seated, are white and male” could benefit from examples or specific actions or reactions to underscore this point.

- Details needed: “She is different than others” can be made more decisive; state how she stands out due to her costumes, relative position to others, and so on.

Suggestions for Concrete Details

- Specify Critical Actions: Instead of saying “there are three-way gazes,” you could describe how the characters fixate on Mary, creating an uncomfortable atmosphere. For instance, you might say, “The teacher’s piercing gaze met Mary’s with a blend of surprise and judgment, while the students exchanged furtive glances, their expressions oscillating between curiosity and hostility.”

- Contextualize Historical References: When mentioning segregation, you might reference period-specific language, such as the word “colored” to illustrate institutionalized racism beyond mere mention of segregation.

- Use Direct Quotes: Integrating direct quotes can lend authority to your analysis. For instance, when the teacher states, “the curriculum is not designed to teach a woman,” you can elucidate the implication of this statement in relation to both race and gender. The teacher does not say a Black woman even though that is what he means.

By implementing these suggestions and reducing repetitive patterns, your analysis will become more compelling and precise. Feel free to ask further questions or seek clarification on specific aspects.

This is intelligent, appropriate, ethical, and responsible use of AI. If you were to ask AI to simply rewrite your essay but without explanation, you will not learn anything. Here, we are asking AI to do one specific task that it is good at: pattern recognition. We then use this information (as if it is a mirror held up to us) to improve our writing skills.

Next Steps: Consult the chapter on critical writing to hone your writing skills. Read also the chapter on close reading to learn how AI “reads” differently from humans.

Bonus: Let us take a look at Professor Alexa Alice Joubin’s lecture on AI and the Craft of Writing:

Further Reading

Chiang, Ted. “ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of the Web.” The New Yorker, February 09, 2023.

“Critical Thinking in the Age of AI,” MIT Horizon, March 19, 2024

Modern Language Association, Student Guide to AI Literacy, MLA-CCCC Task Force on Writing and AI, 2024.