How to write critically and effectively

Academic writing in the humanistic disciplines emphasizes thesis-drive and evidence-based arguments. Effective humanities academic writing is characterized by its open-ended queries.

This chapter guides you through the steps to effective critical writing in the humanities. We will explore the fundamental principles of critical writing, including the nature of writing, the structure of writing, and writing strategies.

Inevitably, in this era of AI, we have to develop new methods of thinking and writing. We can produce compelling and meaningful texts through robust, human-in-the-loop writing practices.

Follow these steps and you will become a more confident and fluent writer.

There are two types of writing: 1. to help us think; and 2. to help readers think. The two modes do overlap and build a synergy. The first type is writer-oriented writing, and the second type is reader-oriented writing. Writer-oriented writing helps the writer themselves clarify their thoughts and understanding of the world. Reader-oriented writing deepens the reader’s understanding of a subject. Oftentimes, reader-oriented writing challenges presuppositions and aims to change the reader’s mind.

One common misconception is that writing is merely a vehicle for asynchronous communication. In fact, writing is not simply putting words on paper to express pre-formed thoughts. We refine our ideas through writing. We discover what we think through writing. As Steven Mintz argues in Writing Is Thinking, “writing is not merely a mode of communication. It’s a process that … forces us to reflect, think, analyze and reason.” This is similar to how language itself shapes our worldview. Language makes certain thoughts possible or more difficult.

Case Study: Academic Writing

Academic writing is governed by genre conventions and a structure of Introduction, Body of Argument, and Conclusion.

The introduction would provide contexts to the open-ended research questions. Some writers offer a “hook” to capture readers’ interest. After providing contextual information (which includes social contexts and what other researchers have published), an effective writer would narrow down and make a compelling thesis statement which explicitly states the arguments of the piece. This section may also provide some insight into why this work (and argument) is important.

The main body of the piece typically delves into case studies that use tangible evidence intentionally to support key arguments. The evidence and arguments progress and connect to one another in a logical fashion. It is helpful to have a blueprint, an outline, before one sets out to write.

It is important to have a meaningful Conclusion which is not just a summary that regurgitates the foregoing paragraphs. An effective conclusion proposes actionable items or questions for further research. It may also apply the thesis (theory) to broader contexts. This is not the place to introduce new concepts or evidence.

Case Study: Writing in an Era of AI

The key concept about AI is augmentation of human capacities. The keyword is augmentation, not replacement. In the right context for the right educational goals, AI could augment and amplify writers’ imagination and meta-cognition. AI would hold up a mirror to the writer to aid in revision processes.

AI educational tools are similar to a training wheel on a bike for us to learn how to ride a bike. It should be used under expert guidance to obtain the greatest benefit. If it is irresponsibly and permanently deployed, the AI training wheel will end up creating an impairment in human writers, diminishing creativity and originality. If we rely on the training wheel, we will no longer be able to ride a bicycle autonomously.

For instance, AI could help non-native speaker writers find ways to express themselves. To be more effective in learning, students should apply meta-cognitive skills to learn those colloquial expressions rather than copying and pasting what AI gives them without examining it meta-critically. AI should be deployed to remove impairments. If AI is used as a shortcut, it could create impairments and permanent intellectual deficiency.

It is challenging to write well in the inquiry-driven culture we live in. Algorithm-governed inquiries and responses frame our contemporary life. Many activities are affected, ranging from navigation to scholarly research. The flow of information is often at stake. As Susanna Sacks and Sarah Brouillette write in “Reading with Algorithms“:

The processes that now structure daily interactions online are cultivated by more-than-human gatekeepers, which apply explicit and implicit logic established by human programmers to determine what kind and whose cultural productions are promoted.

In terms of the prevalent demand for Search Engine Optimization (SEO), we need to resist the urge to write for reading machines rather than for human readers. Charles Pidgeon points out that, as writers strive to produce writing that is both literary and “engaging” as defined by SEO algorithms, they end up producing “a type of writing that opens with an attention-grabbing gambit in line with the logic of SEO.” If we consider the history of SEO, algorithmic-governed ranking mechanisms, and generative AI tools that “read” and survey the Internet, we can begin to see “SEO-boosting, prompt-generated texts” within “a larger story of how internet writing conforms to, resists, or subverts the pressure to optimize for machine readability.”

Understanding the operation of AI helps us become more effective writers. Since generative AI produces outputs that are based on prompts, it is a form of auto completion that builds upon and extends the prompts. The quality of AI output, therefore, correlates highly with the quality of the query or prompt.

One of the most notable features of this type of AI technology is its natural language interface. Since generative AI produces outputs based on prompts, it is a form of auto completion that builds upon and extends the prompts. The quality of AI output, therefore, correlates highly with the quality of the human-initiated query with contextual details. Moving forward in this inquiry-driven search culture, higher-level critical questioning skills are more valuable than basic skills of fact retrieval. Tasks such as pattern recognition and summarization of info are increasingly given to machines.

Understanding the operation of AI helps us become more effective writers. Current AI technologies are designed to accomplish limited and context-specific discursive and simulative tasks. Tools such as ChatGPT are aesthetic instruments rather than an instrument of reason or an epistemological tool. Generative AI is not reliable or trustworthy in new knowledge creation, but its power can be harnessed to recognize patterns in large datasets, to simulate social situations, to trigger human creativity in the arts, and to regurgitate information from datasets it trained on.

While AI is not a reliable tool for cognitive tasks, it can be used for rehearsals, especially in drama education. When accuracy is not at stake, AI could become useful. For instance, we could, through elaborate prompts and setup, have AI do role-playing with humans to test out various dramatic situations or even social scenarios.

A team at MIT designed “AI Comes Out of the Closet,” a large language model-based online system, to help LGBTQ advocates. The system leverages artificial intelligence-generated dialog and virtual characters to simulate complex social interaction simulations. “These simulations allow users to experiment with and refine their approach to LGBTQIA+ advocacy in a safe and controlled environment.” This is an innovative use of AI as a laboratory for humanity.

Further, in early stages of writing, it can be used as a form of social robotics or for social simulation. We could test the drafts of our writing by conversing with carefully calibrated AI (through elaborate prompting) to have it serve as a sounding board to gauge possible reactions to what we write. We can treat AI as a social surveillance instrument, since its output represents the means of common beliefs and biases within a society.

It is not advisable to rely on AI for cognitive tasks, but AI could be suitable for certain non-cognitive tasks. Cognitive tasks require a person to process new information and apply it on new cases. In contrast, non-cognitive tasks may involve routine and formulaic types of writing or pattern recognition.

The randomness of large language models can inspire human creativity by suggesting less frequently trodden paths or uncommon association among objects and words. Some artists have taken advantage of and amplified AI’s randomness as an asset. Mark Amerika uses a predecessor of the current ChatGPT as a co-writing buddy to add layers of “creative incoherence” to his works (Amerika 2022). He uses AI to “defamiliarize language for aesthetic effect” and to increase his work’s “glitch potential,” a process which he compares to the common jazz practice of “intuitively missing a note to switch up the way an ensuing set of phrases get rendered” ( Amerika 2022: 5). One might say Amerika is performing opposite the generative AI in an improvised concert.

Case Study: Writing about Film

More specifically, when writing about films, focus on critical analysis of a film’s components and their (un)intended effects rather than on subjective and evaluative rankings (in the sense of “thumb up” or “thumb down”). Base your analysis and arguments on close observations.

When you write about movies, “it is insufficient to convince others to like or dislike the film, but to add to their understanding of the film,” as Tom Corrigan reminds us.

In other words, “personal feelings, expectations and reactions may be the beginning of an intelligent critique, but they must be balanced with rigorous reflection on where those feelings and expectations and reactions come from and how they relate to more objective factors concerning the movie in question: its place in film history, its cultural background, its formal strategies… what is interesting is not pronouncing a film good or bad but explaining why” (Corrigan).

Focus on one scene. State the “messages of the sequence,” i.e. what is the filmmaker trying to communicate beyond plot elements? Explain how the messages are communicated through cinematography, camera angle, blocking, musical soundtrack, and language.

To build a solid foundation for film analysis, first describe what you see in the sequence. How do cinematographic elements work together to communicate the message? Is space—landscape or interior or set—used as a “comment” on the character’s inner state of mind? Does the use of space exude a certain atmosphere? Are there any symbolic uses of props? What are some of the social and cultural codes?

Your Turn: Vanishing Half

First, let us try textual analysis. Read an excerpt from Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett, a novel about “twin sisters who ultimately choose to live in two very different worlds, one black and one white.” Published in 2022, Vanishing Half is the #1 New York Times bestseller and a women’s prize finalist. Stella becomes white and Desiree marries “the darkest man she could find.” The racial tension is described with light touches, such as “The twins used to love hiding behind the quilts and sheets before Desiree realized how humiliating it was, your home always filled with strangers’ dirty things.”

Bennett’s novel explores the American history of passing, a sensitive topic. Characters in the novel seem both bound by traditional notions of identity and free to construct their own categories. They change but also retain a core part of their unchanging selves.

Another theme the novel touches on is performative identity. In daily life, the characters perform various roles. Sometimes, they are compelled to do so. At other times, they perform these roles voluntarily.

Between these performances emerge their selves that have alternately been erased or reinforced. They struggle between societal expectations and their own aspirations.

In your analysis of the excerpt, pay attention to metaphors of difference and how the story unfold.

Your Turn: Film Analysis

Next, let us try film analysis. Film is a type of cultural text, but with its own distinct grammar and conventions. In contrast to textual analysis, film analysis calls for composite analysis of elements beyond the printed or spoken words: costumes, set, lighting, sound and music, camera angle, and camera movement. For example, we can analyze how the shots contribute to the overall effect of a scene. Here are three sample analyses.

Incorrect description of a shot

Medium shot of a woman standing outside. Cut to a close-up of a dress behind a window. –> Sentence fragment.

Correct

After a medium shot of a woman standing outside a window, the film cuts to a close-up of a dress behind the window. –> Complete sentence.

Even better

An eye-line match links a medium shot of a woman looking into a shop window to a close-up of a dress inside. This shot/reverse shot structure reveals her desire for the dress, and prompts the viewer to share this desire. –> Detailed description and in-depth analysis

Watch the following clip. Describe its key techniques. Building on your close reading (observation), critically analyze the message it is trying to convey. The scene comes from Crazy Rich Asians (dir. Jon M. Chu, 2018). Rachel Chu accompanies her boyfriend Nick to Singapore to attend his best friend’s wedding. While there, she goes to lunch at her college friend and confidante Goh Peik Lin’s mansion. As an outsider, Rachel is contending with jealous socialites and quirky personalities.

The following scene at Goh Peik Lin’s home in Singapore depicts quirkiness in many ways. Identify some of the filmmaker’s strategies to convey parody, comedy, and cultural critique.

Your Turn: DeepL

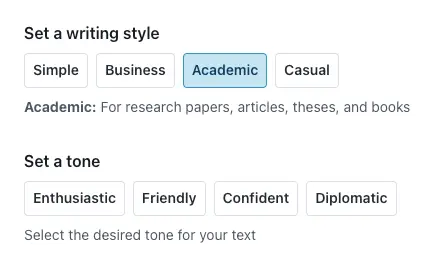

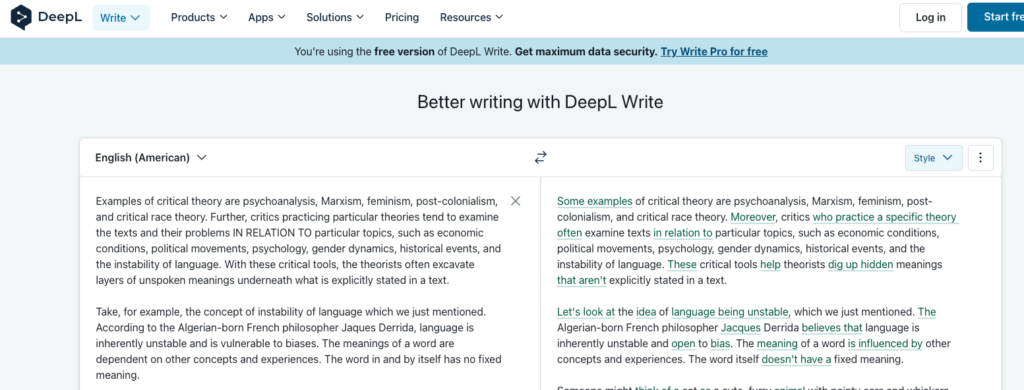

Let us test drive the free version of DeepL, an AI-powered writing tool that can correct your grammar in German, French, Spanish, and American and British English. More interestingly, DeepL can provide suggestions for tone and style. It has various problems, but you can compare your draft to its revisions and take its suggestions with a grain of salt. On a basic level, DeepL can serve as your sounding board at the early stage of writing.

The screenshot below shows Professor Joubin’s experiment with DeepL. On the left is her original text. On the right, with blue markings, is a series of revision suggestions by DeepL. She selected the option to make her text more “casual” in tone.

The Modern Language Association (MLA) regards “ethical and effective use of generative AI technologies” as “an essential skill” today. Here are some highlights of the MLA’s definition of AI literacy:

- You have a basic understanding of how generative AI technologies work.

- You evaluate the relevance, usefulness, and accuracy of generative AI outputs. (You select strategies appropriate to the context, purpose, and audience for a task. ::: You can analyze generative AI outputs to determine whether the results align with the purpose of a task.)

- You monitor your own learning as you use generative AI tools. (You understand and can articulate why you used generative AI in a writing, reading, or research task. ::: You can explain how using a generative AI tool for writing contributed to your work.)

- You recognize that generative AI is fundamentally different from human communication. (You can evaluate whether the output from a prompt used as part of your writing process might result in miscommunication.)

- You understand the potential harms of generative AI, both those inherent to the technology and those that arise from misuse.

— Read more in Student Guide to AI Literacy

Your Turn

Now, use the proprietary AI Teaching Assistant attached to this website to make your writing more effective and impactful. We should amplify AI’s strongest suit: pattern detection. Do not ask AI to write for you or to rewrite your prose. Ask it to help you detect patterns in your writing to enhance your personalized learning.

Here is a sample prompt:

Play the role of a writing tutor to help me enhance the precision of my writing. This is for a university course on critical theory. I need your help to detect repeated patterns in my writing and list them as bullet points. I want to know if I use certain words or certain phrases repeatedly or repeat certain statements. I also need to write with more concrete details and avoid general statements. Restating an idea without developing it does not make it a strong argument. The context is that I am analyzing a scene from the film _____. Please look into the screenplay and point out how I can make my observation of the scene more concrete and compelling. Here is my draft:

The AI here has been trained on the screenplays of the films we discuss in class, the assigned readings, and transcripts of the professor’s lectures. Therefore, it is a trustworthy tool compared to general-purpose AI chatbots.

To become better writers, we first need to become aware of patterns in our own writing. Some words that are used repeatedly by students (often unconsciously) include “clearly” or “throughout history.”

Here is the AI’s response to the prompt above (and a sample student essay in Hidden Figures). It provides feedback on patterns:

To enhance the precision of your writing on the scene, I have analyzed your draft and the screenplay. Below are observations regarding repeated patterns, specific word usage, and suggestions for incorporating concrete details.

Repeated Patterns & Word Usage

- Repetition of Terms: The phrases “race and gender” and “intersectional” appear frequently but without definition.

- Consider varying your language. The term “teacher” could be replaced with the character’s name to increase specificity.

- Precision: Phrases like “All the students, already seated, are white and male” could benefit from examples or specific actions or reactions to underscore this point.

- Details needed: “She is different than others” can be made more decisive; state how she stands out due to her costumes, relative position to others, and so on.

Suggestions for Concrete Details

- Specify Critical Actions: Instead of saying “there are three-way gazes,” you could describe how the characters fixate on Mary, creating an uncomfortable atmosphere. For instance, you might say, “The teacher’s piercing gaze met Mary’s with a blend of surprise and judgment, while the students exchanged furtive glances, their expressions oscillating between curiosity and hostility.”

- Contextualize Historical References: When mentioning segregation, you might reference period-specific language, such as the word “colored” to illustrate institutionalized racism beyond mere mention of segregation.

- Use Direct Quotes: Integrating direct quotes can lend authority to your analysis. For instance, when the teacher states, “the curriculum is not designed to teach a woman,” you can elucidate the implication of this statement in relation to both race and gender. The teacher does not say a Black woman even though that is what he means.

By implementing these suggestions and reducing repetitive patterns, your analysis will become more compelling and precise. Feel free to ask further questions or seek clarification on specific aspects.

This is intelligent, appropriate, ethical, and responsible use of AI. If you were to ask AI to simply rewrite your essay but without explanation, you will not learn anything. Here, we are asking AI to do one specific task that it is good at: pattern recognition. We then use this information (as if it is a mirror held up to us) to improve our writing skills.

Further Reading

Modern Language Association, Student Guide to AI Literacy, MLA-CCCC Task Force on Writing and AI, 2024.

Pidgeon, Charles. “SEO and the essay: what does it tell us about “AI”-generated text and literary culture?” Post45, December 8, 2023