How to Ask Effective Research Questions

What is an effective research question?

Critical questioning skills are very important the age of AI that we live in. High-quality prompts for AI and open-ended social inquiries are crucial to social progression and individual enrichment.

We live in an inquiry-driven culture, in the sense that our social activities are driven by a search culture that relies on high-quality queries. If you have ever used digital maps to look up directions or traffic patterns, used Google to find credible sources to help you answer some questions, or used conversation-based generative artificial intelligence, you are part of this query-driven culture.

In this chapter, we will learn how to formulate effective research questions, which is the foundation for critical thinking.

Inquiries lead to new data and new knowledge about the world we live in. Questions are as valuable as traditional data points, because questions are data as well.

The first step to formulating effective research questions is to carefully read the assigned article or to watch the film twice. Ask yourself: What have I learned? How has this piece or film challenged what I thought I knew about a topic? Put this into bullet points. This summary could provide a foundation for more in-depth questions later. For example, we can progress from a summary of what a piece is about to questions about larger histories or cultural experiences the piece gestures toward but does not fully explore.

Sample Research Questions

There are five types of questions you can ask.

- First, the HIDDEN questions.

We can look for questions that the writer and filmmaker allude to but do not pursue. We can elaborate on one of these “hidden” questions. Scholarship often begins by posing questions, explicitly or implicitly, about current conversations about a topic.

- The second type of research questions: KEYWORDS.

Identify some keywords in the reading or key themes in a film. Do they propose innovative definitions for familiar concepts? Are there gaps in their definitions? Might you add nuance to a concept or theme being portrayed?

- The third type of research questions is called the LARGER ISSUE question.

Read the piece carefully in order to identify larger issues the piece addresses. Ask yourself this: Do I accept their challenge to the conventional wisdom? What are the intellectual stakes of their claims? What are the practical implications of their challenge? For example, if a piece uses a feminist lens to examine representations of white women, you may raise intersectional questions about the theory’s implication on, or exclusion of, women of color.

- The fourth type of research question is all about making connections.

As you read, try to draw connections among different pieces. Ask questions that link them together. This is called the cross-pollination of ideas, which is a key factor that drives intellectual growth. We may ask: How do the readings or films complement each other? How do they speak to each other? Do you see unexpected convergences among them? Or unexpected divergences?

- The fifth type is the personal experience based question.

Last, but not least, there is the research question that draws on your personal experiences. Scholarship is not produced in a vacuum, and your personal experience can be very valuable and a good place to start. What do you know about the topic before reading this piece? After reading it, how does the piece change your view on the topic? What experiences have you been working with that might speak to our readings?

Experiential and contextual questions are very valuable in the humanities. Social context is very important for knowledge production. The types of questions a researcher may ask are often influenced by their culture and worldviews. Different research questions would require different research methods. Different types of questions about the same phenomenon, for example, lead to different answers.

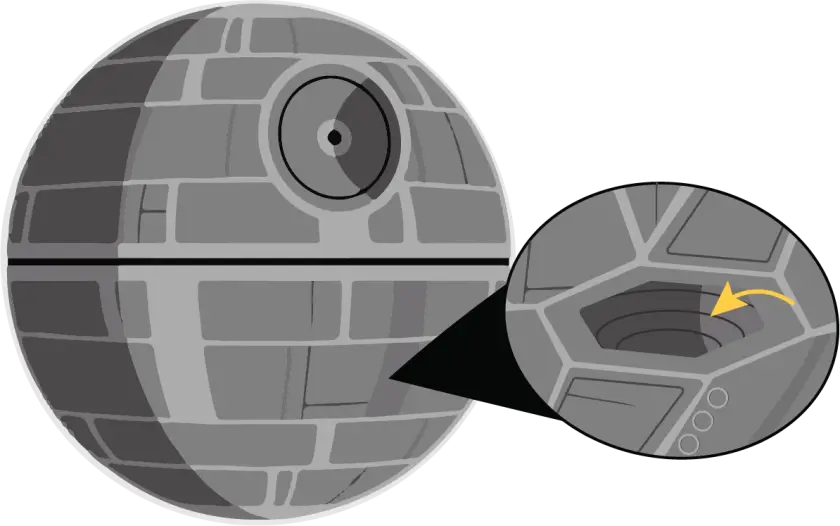

Lesson from Star Wars

What makes a research question effective? A powerful question strikes a balance between openended-ness and specificity. Tackle questions that have broad implications, rather than big questions that say everything yet nothing. In Star Wars IV, Luke Skywalker and his team are trying to destroy the Empire’s Death Star. They are outnumbered and outgunned, yet they accomplished this task by leveraging a small but important spot. They fire two proton torpedos into a narrow, exhaust shaft that leads to the reactor core. They do not take on the entire Moon-sized weapon of mass destruction. They focus on one single spot.

Coda

What is the significance of research questions? Science, broadly defined, is flawed, because it is a human enterprise which inherits human biases. In the humanities, scholars embrace this feature, because it is part of the study. As Julia Belluz and Steven Hoffman argue, science is a social and “human construction” that is “inevitably flawed” because it is “carried out by people, and people are flawed.”

Give it a try yourself

Read the excerpt on essentialism and formulate a research question. Try to go beyond binary questions such as Is essentialism reductive?

In the chapter on What Is Critical Theory? of this open-access textbook, we read Neil McCaw’s “Reading Critical Theory,” which covers Teresa de Lauretis’ feminist theory in 1990. She argues that post-structuralist feminism is problematic because of their advocacy of a female essence. After defining the term essentialism, de Lauretis proposes the idea of the female-embodied social subject as a solution to the contradictions within feminist thinking in relation to ideas of essence. Here is an excerpt from de Lauretis’ text (1990):

Nowadays, the term essentialism covers a range of metacritical meanings and strategic uses that go the very short distance from convenient label to buzzword. Many who, like myself, have been involved with feminist critical theory for some time and who did use the term, initially, as a serious critical concept, have grown impatient with this word – essentialism – time and again repeated with its reductive ring, its self-righteous tone of superiority, its contempt for ‘them’ – those guilty of it.

Yet, few would deny that feminist theory is all about an essential difference, an irreducible difference, though not a difference between woman and man, nor a difference inherent in ‘woman’s nature,’ (in woman as nature), but a difference in the feminist conception of woman, women, and the world. Let us say, then, that there is an essential difference between a feminist and a non-feminist understanding of the subject and its relation to institutions; between feminist and non-feminist knowledges, discourses, and practices of cultural forms, social relations, and subjective processes; between a feminist and a non-feminist historical consciousness.

That difference is essential in that it is constitutive of feminist thinking and thus of feminism: it is what makes the thinking feminist, and what constitutes certain ways of thinking, certain practices of writing, reading, imaging, relating, acting, etc., into the historically diverse and culturally heterogeneous social movement which, qualifiers and distinctions notwithstanding, we continue with good reasons to call feminism. Another way to say this is that the essential difference of feminism lies in its historical specificity – the particular conditions of its emergenceand development, which have shaped its object and field of analysis, its assumptions and forms of address; the constraints that have attended its conceptual and methodological struggles; the erotic component of its political self-awareness; the absolute novelty of its radical challenge to social life itself.

What is your take on essentialism after reading this theoretical text? Would you write a research question based on personal experiences, that make connections between different theories, that focus on large issues, that take a closer look at the keyword, or that draw attention to what is not said (“hidden questions“)?

In summary, in this unit, we have learned about

- The inquiry driven culture we live in

- Five types of effective research questions –

- The hidden questions

- Questions about keywords

- The larger issue questions

- Questions that make connections

- Questions that draw upon your personal experiences

Now, it is your turn. Read the assigned text. Draft a research question to the best of your ability. To beta-test it, you may use a generative AI tool to see how might your question be answered and how you might fine tune your question.

For example, you can use this prompt in the freely accessible version of ChatGPT:

Please play the role of a college professor to give me feedback on the quality of my research questions. This is for a humanities course. I have to come up with open-ended, sophisticated research questions about the assigned readings. Please provide possible answers to my draft question. Then, please provide three alternative, more open-ended versions of my question. My research question is …

When a student tested their draft question of “When film adaptations update Shakespeare’s plays to appeal to contemporary audiences, are they being unfaithful to the original content?” They received the following output.

=============

Feedback on Your Research Question:

- Strengths:

- It tackles a specific and relevant topic.

- It invites analysis and discussion, rather than a simple yes/no answer.

- It engages with the theme of adaptation, which is rich in academic discourse.

- Areas for Improvement:

- The term “unfaithful” can be subjective and might need clarification within your research.

- The question presupposes a binary (faithful/unfaithful) that might limit the depth of exploration.

Possible Answers:

- Yes, they are unfaithful: Film adaptations often make significant changes to language, setting, and character motivations to appeal to contemporary audiences, thus diverging from the original text’s intent and nuances.

- No, they are not unfaithful: These adaptations can be seen as a continuation of Shakespeare’s work, bringing his themes and stories to new audiences in a manner that preserves the essence of the original plays.

- It depends: The faithfulness of an adaptation can vary depending on the director’s vision, the context of the adaptation, and the specific elements of the play that are changed or preserved.

Alternative, More Open-Ended Versions:

- How do contemporary film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays reinterpret the original texts to reflect modern societal values and issues?

- This version invites a broader exploration of how adaptations reflect contemporary culture and values, rather than focusing solely on fidelity to the original.

- In what ways do film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays navigate the balance between staying true to the source material and making the story accessible to modern audiences?

- This question allows for a discussion on the creative process behind adaptations and the various factors that influence how the source material is transformed.

- What are the impacts of updating Shakespeare’s plays in film adaptations on our understanding and appreciation of the original works?

- This invites a broader analysis of the consequences of adaptations on the reception of Shakespeare’s plays, encouraging exploration of both positive and negative impacts.

These alternative questions aim to open up a wider range of discussions and perspectives, allowing for a deeper and more nuanced exploration of the topic.

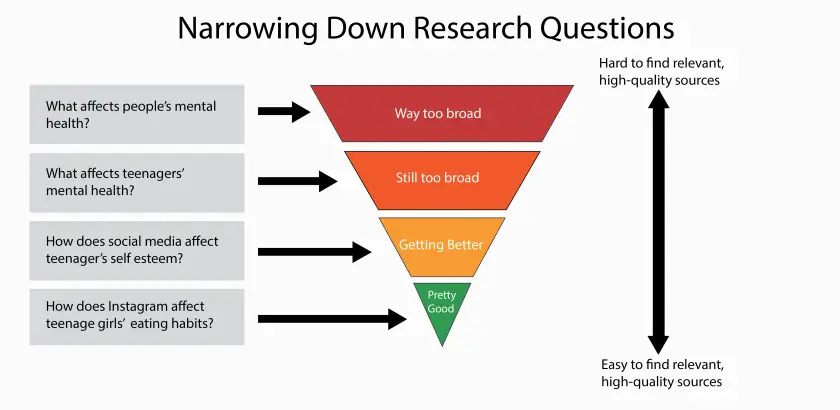

The key here is asking open-ended yet specific-enough research questions to build a project worth pursuing. The following infographic shows you the four stages of narrowing down a research question.

As shown in the illustration above, big questions may be interesting but they lack specific details. Without details, one does not have a compelling project. Typically you can start to provide details by narrowing down on historical periods, cultures, and genres. In some context, generative AI can serve as a sounding board for you to test out different versions of your question as you fine tune it.

Your Turn Again: CODA

Let us formulate an open-ended but sophisticated research question regarding the audition scene in Sian Heder’s 2021 film CODA. The film won three Oscars for the Best Picture, Best Supporting Actor, and Best Adapted Screenplay.

The school choir teacher encourages the protagonist Ruby, a hearing Child of Deaf Adults (CODA), to audition as a vocalist for the prestigious Berklee College of Music. Her family, initially reluctant, shows up, to her surprise, to support her in this pivotal moment. During the audition, Ruby sings “Both Sides Now” by Joni Mitchell (see the lyrics here).

As you draft your research question, consider both interpretive and artistic aspects of the scene. How is the scene presented cinematically? What effect does it have on film audiences? For whom does Ruby seem to be singing? How does the scene–devoid of verbal language (no one is talking)–integrate sign language and the language of music?

Director Heder says, during an interview, that “disability is only created when a culture does not make it possible to participate.” What does this statement mean to you after watching this scene? How does such a scene, with three groups of people relating differently to the world, deconstruct compulsory able-bodiedness?

Further Reading

Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams, Craft of Research, 2nd edition (University of Chicago Press, 2008)

Mullaney, Thomas S. and Christopher Rea, Where Research Begins: Choosing a Research Project That Matters to You (and the World) (University of Chicago Press, 2022).