A History of Race

The Blessing and Curses of Categorization

Humans come to know and experience the world through various categories that organize the world into knowable fragments. Knowledge about otherness is socially constructed and justified to serve specific ideologies. Knowledge of race results from taxonomical observations made for colonial, medical, bureaucratic, or other purposes such as political movements.

This knowledge is often articulated in the form of inaccurate stereotypes deriving from perceived behavioral patterns, political shorthand that condenses biological features such as skin color and other bodily characteristics, racialized cultural artifacts such as hip-hop or chopsticks that are associated with particular groups or cultures, and check boxes on government forms that require information that encode racial characteristics.

People tend to think in terms of categories that help them to demarcate differences. In the process, we also shape the world with the language we use to describe it. Inevitably, some narratives privilege the storyteller’s own cultural location as a superior center and the rest of the world as inferior and peripheral.

Racial Mythologies

This feature makes race a “relational” category. Embodied identities signify relationally. That is to say, we tend to define our identity against what we are not. As is often the case, without contact with other people or without the threat from other groups, there is generally no perceived need for self-definition.

There is a racist tendency that is especially evident in myths about the origin of human races in various cultures. In Chinese Daoist mythology, there is a prominent figure of giant known as Pan Gu (read more on British Museum’s site), the first man and the creator god. In one version of the mythology, Pan Gu’s corpse gave rise to the universe, with his eyes becoming the sun and moon and his blood forming rivers. Human races evolved from parasites on his body with hierarchical implications. These creation myths date from the 3rd to the 6th century. Here is an 18th-century woodblock print of Pan Gu made in Guangzhou, China.

Case Studies

According to a Chinese myth, different skin tones are related to accidents in the creation process. When the gods created humans out of clay figures, they initially left the clay in the kiln for too long. The figure came out burned and black. The gods threw it as far as they could, and it landed in Africa. They took the second figure out of the kiln too soon, which is pale and white. They threw it away, and it landed in Europe. Once the gods determined the correct timing, they created the perfect figure in gorgeous yellow, who became the ancestor of the superior East Asian yellow races.

Along a similar vein of constructing racial hierarchies, early modern Europe devoted significant social energy to the idea of “blue blood,” an idea about racial purity, or sangre azul in Spanish. The nobility’s “blue” veins are visible through their fair skin, because, according to this ideology, their lineage has never been “contaminated” by Moorish or Jewish blood.

Becoming Black

Is one born black, or does one become black?

Racialized thinking is often a projection of one’s desires, ambitions, anxieties, or ignorance. In pre-modern China, peoples of many ethnicities “became” black in the Chinese consciousness. Increased cross-cultural contacts seemed to have only broadened the idea of blackness. In the Tang Dynasty in the seventh century, Chinese writers labeled numerous peoples “black.” It’s a capacious notion of Blackness.

Initially the Nam-Viet peoples and Malayans, China’s Southeast Asian neighbors, were designated black in the Tang dynasty, but with China’s increased encounters with slaves from Africa (modern-day Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania) from the seventh to the seventeenth centuries, the “blacks” in Chinese consciousness expanded to include peoples from various parts of the world, including Bengali peoples of the Indian subcontinent.

European observers associated red with American Indians’ skin color because of their war paint and because of the sun-screening substance they used to anoint themselves. American Indians became red when the need for distinction between the European settlers and the natives arose.

Meanwhile when the West encountered African culture in the sixteenth century, “the most arresting characteristic of the newly discovered African was his color. Travelers rarely failed to comment upon it.”

Becoming “Yellow”

Likewise East Asians became “yellow” after the eighteenth century physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach categorized them as such. The pseudo-scientific classification of human features during the enlightenment and epistemologies of race derived from them formed a mutually validating and energizing synergy. The system of knowledge that emerges from this combination is then put to political use.

As Michael Keevak observes, “there was something dangerous, exotic, and threatening about East Asia that yellow … helped to reinforce, [as the term is] symbiotically linked to the cultural memory of a series of invasions from that part of the world.”

Intra-Group Racism

Since racial identities signify relationally, a group that suffers from discrimination can themselves discriminate against other groups based on any combination of the factors of race, class, gender, and religion.

Take East Asia for example. While Taiwanese women are fighting for economic and social equality, at the same time they are known to mistreat their darker-skinned live-in Indonesian and Filipino maids. As Taiwan was integrated into the global economy, average households in Taiwan began hiring Southeast Asian helpers. This has simplified the gendered household burden for more privileged women. However, it has also complicated the racial and class divisions of domestic labor and led to racism. Learn more in Pei-chia Lan’s Global Cinderellas: Migrant Domestics and Newly Rich Employers in Taiwan (Duke University Press, 2006).

Along similar lines, there is the phenomenon of what is sometimes called internal racism, or intra-group hatred, where a community has internalized its former colonizer’s outlook. In politically post-colonial but culturally colonial societies such as Singapore, where the state apparatus openly uses race as a category in its promotion of institutionalized multiculturalism, whites are typically placed above the local race in the social hierarchy while darker-skinned migrant workers are placed below.

Your Turn

Using what you learned about the history of race to analyze the following scene from Green Book (dir. Peter Farrelly, 2018). The film follows the concert tour of Dr Don Shirley to the American South in 1962. Dr. Shirley is a world-class African-American pianist. He recruits Tony Lip, a tough-talking bouncer from an Italian-American neighborhood in the Bronx. Despite their differences, the two men soon develop an unexpected bond while confronting racism and danger in an era of segregation.

In the following scene, “I’m way blacker than you,” while on the road, Dr. Shirley and Tony erupt into a heated debate about race, identity, and acceptance in a segregated and racist world. Why do they launch into this debate and “competition”? In the scene what does Blackness refer to? Between Dr. Shirley and Tony, who is right, in your opinion?

Conclusion

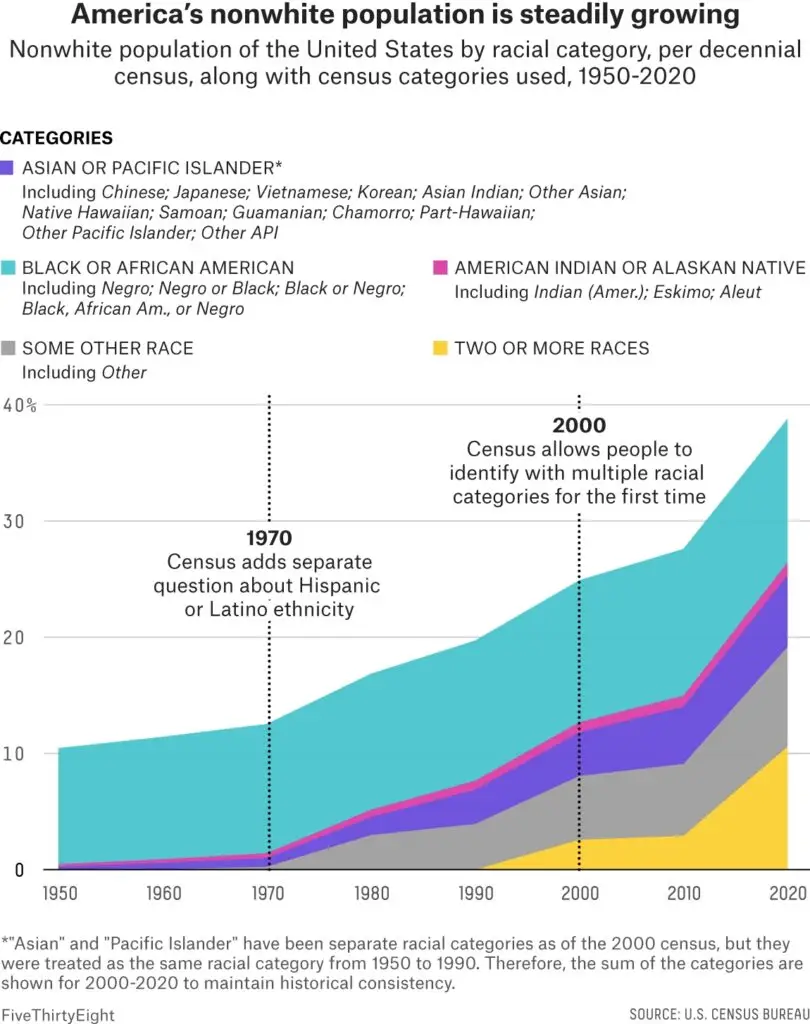

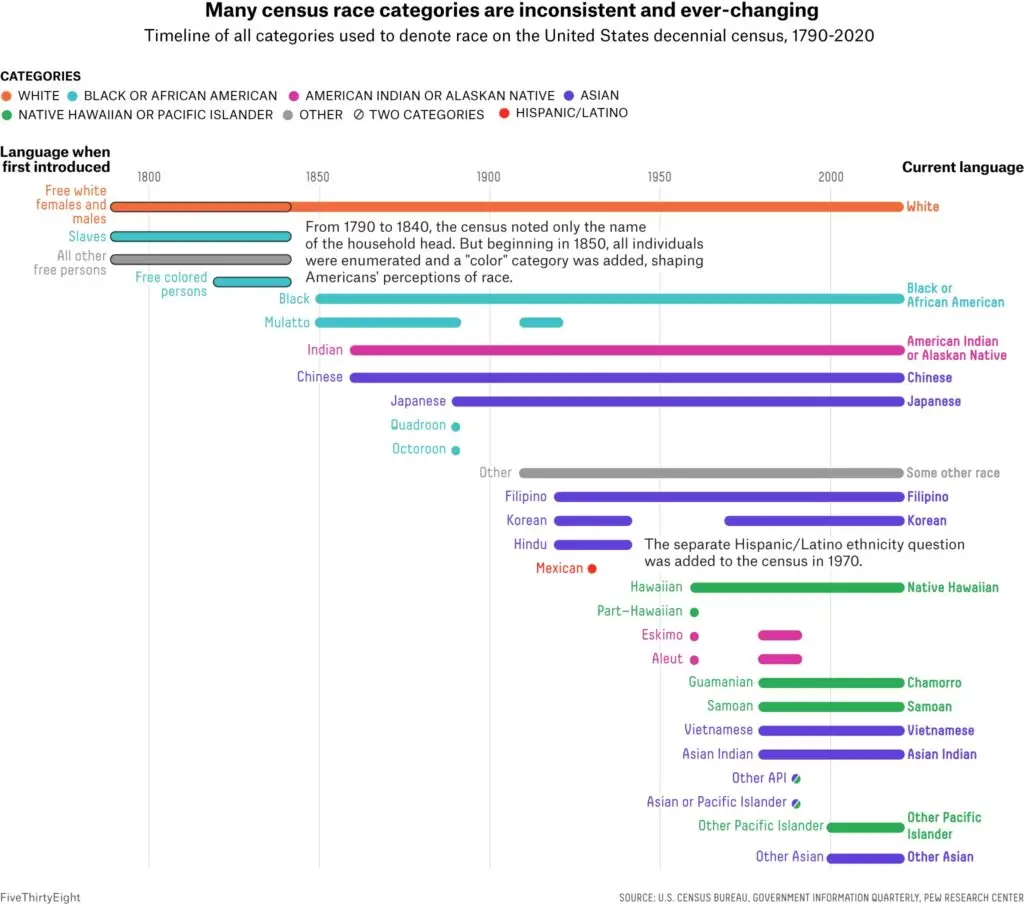

Ethnicity is often defined in tandem with race, as evidenced by the evolving categories in the US Census. Even how racial identities are listed has been very uneven. Only in 2000 did the Census allow people to identify with multiple racial categories for the first time. In the 2020 Census, “Middle Eastern” was subsumed under white.

Projects to define race are complicated by a symbiotic relation between definition and self-fulfilling prophecy, between typology and racism. But there is a bright side: Thinking through race estranges what is taken for granted.

Why do we study histories of race?

The construction of race is a process of responding to the demands of others. It may take the form of subjugation or oppression. It is a process of negotiation. We study race historically not only to find roots of modern racism, but also to discover other views that may have been obscured by more dominant ideologies such as colonialism.

Literary and historical texts contain traces of these alternative perspectives and past debates. Reading histories of race may be a passive act, but if it leads to recognition of one’s self in others, then our job as critical analysts is done.

Here are details of the growth of multiracial communities in the US (graph on the left) and of how inconsistent and ever-changing the census race categories have been (graph on the right) from 1790 to 2020. The graphs are called Who the Census Misses.

Further Reading

Some of these resources may only be accessible with George Washington University credentials.

Delgado, Richard, and Jean Stefancic, eds., Critical Race Theory: The Cutting Edge, Third Edition. Temple University Press, 2013.

DiAngelo, Robin. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Beacon Press, 2018.

Joubin, Alexa Alice and Martin Orkin, Introduction, Race. London: Routledge, 2019.

Morrison, Toni. The Origin of Others. Harvard University Press, 2017.