AI in Fiction

Fiction is a humanistic lab for thought experiments. There is truth in fiction. It may be a cliché to say that art imitates life (or in the case of science fiction: art precedes life), but fiction has a palpable impact on how society perceives and treats various groups in the real world. AI’s outputs mimics human patterns. Some people accept the outputs because they are deemed just good enough. Others reject them because of mediocracy or even simply for lack of some undefined human touch.

One reason to study AI in fiction and AI as fiction is that a key attribute of generative AI is virtuality. Based on its real-world datasets, generative AI simulates social situations textually and visually, creating a virtual world that mirrors the human world. A key concept here is mimesis, the representation of the real world in art and literature. In ancient Greece, Plato used mimesis to refer to dramatic action in a play. In that context, mimesis carries negative connotation, suggesting concealment, deception, or fraud. However, later philosophers recognize art’s ability to present truth through fiction.

Mimicry, a related concept, refers to mockery. In postcolonial studies, mimicry describes the paradoxical (or doubly articulated) state of affairs in colonial countries. The colonized adapt the language and culture of the colonizer with twists. As Homi Bhabha theorizes, mimicry is “an ambivalent strategy whereby subaltern peoples simultaneously express their subservience to the more powerful and subvert that power by making mimicry seem like mockery” (see Ian Buchanan’s A Dictionary of Critical Theory).

It is in this sense we can use Michel Foucault’s theory of heterotopia to analyze AI’s outputs. As heterotopia, or worlds within worlds, plays depict worlds that resonate with or contradict our world in powerful ways. Generative AI produces artifacts that are at once real and unreal in the sense that they exist in a virtual world. With their multiple layers of cultural meanings, heterotopia expand and contract based on their tacit and explicit relationships to other places.

Generative AI is suitable for “fuzzy” tasks that do not require precision. As a form of social robotics, it’s a social simulation and social collaboration tool. While the field of AI is dominated by white men, AI could be a tool to promote equality and inclusion. There are significant, yet overlooked, connections between AI and the LGBTQ community. As D. Pillis writes, “computing has always been queer.” There are many queer individuals in this field, including Alan Turing, a founding figure in computer science and AI. Turing faced chemical castration for his homosexuality. Amplifying AI’s capacity to simulate human speeches, Pillis’ team built “AI Comes Out of the Closet,” a large language model-based system to train LGBTQ advocates. The system has virtual characters who enter into conversations with advocates to simulate social interactions in a controlled environment. “There’s something about queer culture that celebrates the artificial through kitsch, camp, and performance,” said Pillis.

Metaphor is another useful critical concept from literary studies that can expand our understanding of our relationships to AI. Metaphors matter, and we should develop more empowering and inclusive metaphors. The work by linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson shows that metaphors are pervasive in everyday language. Metaphors help us understand, as much as they delimit our understanding of, our experiences (see Metaphors We Live By). In the realm of AI, people often use anthropomorphic or anthropocentric metaphors to describe AI’s operation and its relationship to the society.

As N. Katherine Hayles writes in her chapter in Feminist AI, “metaphors channel thought in specific directions, enhancing the flow of compatible ideas while at the same time making others harder to conceptualize. Metaphors influence not just what we think but also how we think” (1). Hayles suggests technosymbiosis as a new metaphor for “our relations with humans, nonhumans, and computational media including AI” which “locates human being in relation to other species and the environment” (8-10).

There is a long history of literary and cinematic depictions of artificial general intelligence (AGI) in embodied and disembodied forms. In science fiction and speculative fiction, AI is usually shorthand for AGI, machine learning models that have a wide range of cognitive skills and surpass human capabilities. Frequently explored topics include sentient androids (or robots) and “what makes us human.”

In fiction, AI and humanity are often assumed to be two distinct entities, while AI, like prosthetic limbs, has become part of what it means to be human. One of the prevalent tropes is AI turning against or replacing humanity. Another involves mistreatment of artificial people since they are purportedly “not real.”

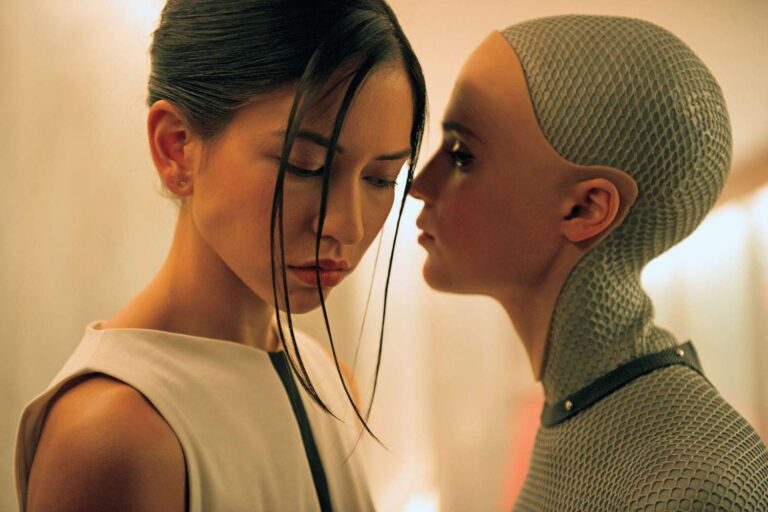

Both of these tropes are found in Ex Machina, a film about humanoids directed by Alex Garland in 2014. A white male inventor named Nathan creates a series of androids with varying levels of AI capabilities. All the androids are in sexually attractive female forms, and many are East Asian. In the next section we will delve into Ex Machina as a case study.

Case Study

The first thing to note about depictions of embodied AI in fiction is the psychological phenomenon of face pareidolia, humans’ tendency to see faces in objects. Consider, for example, the garbage collecting robot in the film WALL.E. Film audiences see a human-like face and project humanity onto the robot. Researchers know of the so-called Goldilocks zone of pareidolia, a type of images that is most likely to induce pareidolia.

The white humanoid, Ava, is shown to be more intelligent than other bots, with a large range of human emotions. With full language function, Ava is very articulate and can express herself through drawings as well. While Ava also obeys her creator, she is far less subservient; she does not do house chores.

In contrast, the Japanese humanoid Kyoko is placed in a subservient role. Kyoko is not only designed to do house chores like a live-in maid, but she is also mute, without a language function. The scenes where Kyoko quietly makes sushi rolls, wipes the dinner table, and is scolded by Nathan depict the symbiotic relationship between racism and misogyny directed toward women of Asian descent.

There is another, equally disturbing aspect of racist misogyny: the stereotyping of East Asian women as untrustworthy, cunning “dragon ladies” or as femme fatales. Toward the end of the film, Kyoko rebels against Nathan and eventually kills him with her sashimi knife. Presenting Kyoko as the ultimate racial and gendered other, the film falls into the trap of techno-Orientalism, a tendency that combines technological fantasies and patronizing attitudes toward the “Orient,” an antiquated term for Asia.

Techno-Orientalism emerged in the 1980s, notably in Ridley Scott’s dystopian sci-fi film Blade Runner (1982). In that film, there is a multi-story-high digital poster of a Japanese geisha in Blade Runner.

Techno-Orientalism is a trope in film and literature that presents Asian people as technologically advanced but emotionally immature. This trope presents a people as both robotic (not quite human) and productive. Further, Asian women in these films often need to be rescued by white men. It is a strong thread in imaginations of AI.

Robotic images of Asian women, such as Kyoko in Ex Machina, contribute to what David Morely and Kevin Robins call “techno-Orientalism.” The concept emerged with the Japanese economic boom in the 1980s, which caused “Japan panic” in the West. Detractors believed that Japan’s “Samurai Capitalism” was “calling Western modernity into question and claiming the franchise on the future.”

In Rupert Sanders’s film Ghost in the Shell (2017), white protagonists navigate futuristic urban spaces that are littered with references to pan-East-Asian script, architecture, and food. Another example is Kyoko in Ex Machina, who is an advanced AI bot but cannot talk or emote since she is designed to be intellectually primitive.

Other screen works also amplify the instrumentality of female Asian figures. Mia is a sentient Asian female android is the lead Channel 4’s series Humans (2015) in the UK. Mia is bought at a shopping mall by Joe Hawkins, an overworked, white father. Mia is tasked with helping with household chores including cooking, babysitting, cleaning, and grocery shopping.

Take a look at the scene below.

Ex Machina and Humans conflate Asian women with fungible objects that one can abuse, subjugate, and sexually exploit without moral burden. Martha Nussbaum defines fungibility as the harmful idea that a person is interchangeable with other objects. In “Objectification”, Philosophy and Public Affairs, 24.4 (1995): 249–291, Nussbaum theorizes fungibility as a key step of objectification, which is the act of treating a person as an object.

The final scene of Ex Machina exemplifies the idea of fungibility, namely some bodies are interchangeable. After killing Nathan, Ava sustains damages to her body. She repairs herself using the skin and parts from other robots. Notably she uses the skin of female Asian robots to patch herself up.

The final shot shows Ava arriving in a big city and blends into the crowd at a crossroad. Not only is Ava’s desire to become human a transgender allegory, but she effectively becomes mixed race with multi-racial skin and parts.

But not all artificial bodies need repair, and not all robots need to become “real.” Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is an anti-transformation adaptation. In the film, Pinocchio does not actually become a “real” boy like his counterpart does in Carlo Collodi’s novel, because he has always been real all along.

Your Turn: Western and Eastern Views on Individuality

How do films construct and convey fears of sentient AIs? How does the figure of AI stoke the desire and anxiety about surrogates of humans?

Use critical AI theory to analyze the following 5-minute scene in Steven Spielberg’s film A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). How does it re-imagine human-machine relations? What attitudes does the film capture and critique?

Spielberg’s film builds upon Stanley Kubrick’s unfinished project and is loosely based on Ian Watson’s 1969 short story. Set in a world experiencing environmental disasters in the 22nd century, A.I. follows the journey of David, a humanoid child robot. David is given to a couple as a surrogate son. The couple’s son Martin is in suspended animation due to a rare disease. As Tim Kreider writes, “David has been given a comforting illusion, like the one Spielberg’s narrator offers us in this ending, if, like children, we choose to believe it” (39).

The scene in the clip below concerns David’s meeting with his creator, Professor Hobby. David is shocked to find copies of himself. He is disheartened and no longer feels he is unique. In fact, as it turns out, David himself is not “original.” Professor Hobby designed David as a replica of his own dead child. For the couple, David is a substitute for their comatose son. At the end of the film, 2000 years later, David comforts himself with a technological simulacrum of his adoptive mother.

What are the implications of fungibility (interchangeability) and simulacra in technology?

Can Inanimate Objects Have “Souls”?

In the Japanese Shinto Buddhist tradition, all beings and objects have souls (kami). In the West, only humans have souls in the classic conception of mind and body.

The scene where David discovers copies of himself depicts the uniqueness mandate and a categorical crisis. In social identity theory, this poses as distinctiveness threat. When an event blurs the boundaries defining an individual’s identity as indispensable, original, and unique, the individual would feel threatened and question the meaning of their own existence. Before walking into that room, David assumes he is the only one of his kind. The definitional boundaries collapse when David discovers he is but one of many Davids.

Let us compare Spielberg’s A.I. and its Western ideologies about individualism to Japanese ideas of individuals as part of and forming communities in Hirokazu Koreeda’s Air Doll (空気人形, 2009). The film follows the adventure of a life-size inflatable sex doll (played by Korean actress Bae Doona) who becomes sentient and comes to life. She is bought by a middle-aged man to keep him company. He names her Nozomi (which means hope). As she explores her apartment, neighborhood, and city, Nozomi carries a similar level of innocence and curiosity about the wider world as Spielberg’s David.

Some scholars have argued that the “deviant” sexual practices with a doll or robot “will encourage similar behaviors with humans,” while other researchers point out such actions can be cathartic and therapeutic. Informing this debate are the similarity of humanoid robots to humans and the human tendency to anthropomorphize objects (Belk).

In the following scene, Nozomi stumbles upon the factory that produces air dolls. She is searching for the answer to what it means to “be alive.” There, she meets her creator–not God but a man, an artist. Upon seeing Nozomi, he says “welcome home!” He then asks her “Do you wish you’d never found a heart?” in reference to her having a soul now. The idea that a doll has a soul reflects the Shinto Buddhist notion of universal souls, or “yaoyorozu no kami” (八百万の神, eight million gods). It implies there are too many deities (kami) to count.

How does this scene differ from, and echo, the scene of David in Spielberg’s film? Nozomi now realizes she is not unique, as there are many copies of her.

AI as Social Robotics

If you could “clone” a loved one in embodied form, would you? Would that concept make humans fungible (interchangeable)? With a similar premise to Air Doll, a child-sized humanoid robot doll powered by artificial intelligence develops self-awareness in M3GAN (dir. Gerard Johnstone, 2022). No cloning is involved in Air Doll or M3GAN, but the two speculative and science fiction films explore the idea of surrogates and humans relations to non-human agents.

While Nozomi in Air Doll explores human life and society once she becomes self-aware, M3GAN in the American science fiction horror film becomes hostile toward anyone (even a dog) whom she deems a threat to her human companion, Cady. Blending horror and campy humor, the narrative recycles the well-known trope of AI designed to serve humans going haywire. M3GAN is designed to be a companion to children, but it ends up harming everyone.

Beyond fungibility, these narratives also examine humans’ emotional attachment to inanimate objects and the artificiality of love. One example is the haunted porcelain doll in Annabelle (dir. by John R. Leonetti, 2014).

Beyond Air Doll and M3GAN, there are several other well-known examples of objects coming to life, such as Chucky in Child’s Play, directed by Tom Holland in 1988 (see trailer here). In the supernatural slasher film, a widowed mother gives a doll to her son. As it turns out, that doll is possessed by the soul of a serial killer. The doll “comes to life” and terrorizes the family.

Does “Simulation” Make Something Less Authentic?

Are simulated (reconstructed) artifacts less authentic or less “real”? Consider the Ship of Theseus, a Greek thought experiment that explores the question of whether an object is the same after all of its original components have been replaced. At the end of Ex Machina, Ava patches herself up with parts taken from decommissioned robots. Is Ava a new “person”?

Another side of the anxiety of fungibility is the fear of not being the “original.” In Duncan Jones’s Moon (2009), Sam Bell works solo on the Moon for Lunar Industries. He experiences a personal crisis and inadvertently discovers his doppelganger, a clone. See the trailer of Moon here.

The notion of fungibility comes to its head in the final scene of Ex Machina. Having killed Nathan and decided to leave Caleb to be trapped and die, Ava walks over to a closet full of retired models of East Asian female androids.

Unlike David in A.I. and Nozomi in Air Doll, knowing that she is not the original or the unique one does not faze Ava. She is interested in saving only herself at the expense of both humans and other androids. She peels off the skin of the Asian androids to patch herself up, and replaces her damages arm with that of one of the androids. Finally, she puts on one of the androids’ dress and escapes the compound to blend into the human society unbeknownst to anyone. Ava becomes interracial or mixed race by virtue of her white and Asian skin tones as well as trans-human by virtue of her final transformation.

Theory of Assemblage

Ava’s processes of self-repair and self-affirmation using salvaged parts also echo the trans / queer theory’s understanding of assemblage. The theory of assemblage holds that human and non-human agency and elements overlap in ongoing processes of identity formation (Puar, 2012). To explain identity, agency, and contingency, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari propose a theory called agencement in French, which is translated as arrangement or assemblage. It suggests that people’s actions are interdependent on one another and within connected legal, economic, and ideological infrastructures. The keywords to understand the complexity of social phenomena are connectivity, fluidity, and interdependence.

This is true of gender practices and expressions. From the perspective of assemblage theory, gender is “an on-going movement where associations with bodies, norms, knowledge, interpretations, identities, technologies, and so on, are made and unmade in complex ways” (Lagesen, 2012, p. 444). In other words, gender is “only a temporary articulation rather than an essential identity category” (Coffey, 2016, p. 33) of fluid associations of material, social and ideological conditions.

Building on this theory, Jasbir K. Puar sees identities and bodies as “unstable entities that cannot be seamlessly disaggregated into identity formations.” There are no pre-determined destinations for identity formation. In other words, assemblage is not the same as assembling a model plane (with pieces of plastic that have pre-designated positions to form an already-conceived structure (the model plane). “An assemblage is a becoming that brings elements together” (J. Macgregor Wise).

Through the process of assemblage, Ava becomes a self-made woman physically and figuratively. This echoes but reverses the process of the inventor assembling Ava shown earlier in Ex Machina (particularly the scene where Nathan holds an AI brain, boasting his God-like power to Caleb). At the end of the film, Ava is all of these things: an AI-driven robot, a patched-up trans-racial being, and a mimicry of her oppressors (humans).

Let us now take a look at the inventor figures in these films who are invariably male.

The doll maker in Air Doll, while being somewhat indifferent to his dolls’ fate in the world, comes off as caring and gentle, at least in his interaction with Nozomi.

In contrast, Nathan, the inventor and tech bro figure in the aforementioned Ex Machina, is depicted as arrogant. He objectifies Ava and Kyoko. All his humanoids are female. He brings in an employee named Caleb to conduct a Turing Test on his AI androids.

In the following scene, Nathan shows Caleb the lab where the AI’s brains are created. Take a look at the scene and compare Nathan to the doll maker in Air Doll.

Does AI need a gender?

Does AI have or need gender or race? Is the figure of the robot an extension of humanity or a surrogate of it? Why do sentient robots in films often want to become “real” humans? Why does the disembodied sentient AI operating system in Spike Jonze’s Her need to be coded feminine and hire a human surrogate to act as her body?

As some filmmakers humanize robots with human-like features, they inadvertently de-humanize women. Many of these synthetic cyborgs and plastic dolls seek to become humans or transcend the carbon-based human existence.

We can use anti-racist feminist theories to examine films featuring artificial bodies from robots to dolls, such as Greta Gerwig’s Barbie whose lead character becomes a “real, biological” woman, the aforementioned Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Air Doll in which a life-size inflatable sex doll comes to life, Spielberg’s A.I. in which a robot child, David, seeks to become real, and Alex Garland’s Ex Machina.

In the following scene in Ex Machina, Caleb asks Nathan why an AI needs a gender. The two launches into a debate about embodied experience and what makes us human.

Speaking as if Kyoko is not there, Nathan explicitly states that the female androids can be penetrated and can sense pleasure, all while hinting at sexual assault. All the humanoids are Nathan’s prisoners, as they are confined in his remote, underground mansion. Kyoko, the Japanese-presenting android, stands out. She cannot speak. She cooks, cleans the house, and serves meals to Nathan and his guest, Caleb. The dishes she prepares align with her given racial identity: Japanese cuisine with an emphasis on sashimi and sushi rolls.

Depictions of AI in these films are informed by each culture’s view on individualism and individuality. They do raise some common question but offer different answers: Is each AI-powered humanoid unique and irreplaceable? What are the implications if there are many exact copies of an AI bot? Are humans also fungible?

Your Turn Again: The Matrix

Use critical AI theory to analyze the body politics and postmodern technological embodiment in the following two scenes of interrogation and rescue from The Matrix (dir. Lana Wachowski and Lilly Wachowski, 1999), a science fiction film in which artificial intelligence requires the nourishment of human bodies as a crucial source of energy. The film echoes Anne Balsamo’s theory of the techno-body, human body enhanced or supported by technological prostheses.

Among the different types of technological embodiment in Balsamo’s theory is the marked body, a body that becomes a sign of culture which, in turn, becomes a commodity. In the Matrix, human bodies bear signs of the cultural past of human civilizations only to serve as an energy source for the machines.

Another type of body that is relevant to this film is the repressed body which is controlled by virtual reality applications (Balsamo 228). While the battle occurs in the Matrix, a virtual reality space, infliction of harm on the virtual body affects the real bodies outside the Matrix; when Neo’s avatar is hurt in the Matrix, his body sustains injury in reality.

In the first clip, the Interrogation Scene, Agent Smith interrogates and tortures Mr. Anderson, the avatar of the protagonist Neo in The Matrix. The secret agent violates Mr Anderson’s body by melting his mouth shut and planting a metallic tracker bug into him through his umbilicus. One way to read this scene might be to think of it as a metaphor for rape.

In the second clip, Trinity rescues Neo. While escaping in a car, she uses a portable device that resembles an ultra sound machine to examine Neo’s abdomen. Upon locating the tracker bug, which has now become biological, Trinity extracts it. The bloody bug is trapped in a glass tube, which resembles an embryo. One way to interpret this scene might be to read it as a metaphor for abortion.

There are many other possible interpretations. In your analysis, examine the ways in which these scenes depict the human-machine relationships.

Theory of Simulacra

The Matrix is a simulation program, or a simulacrum of the human past. As a meta-fiction (fictional, virtual world called the matrix inside a larger narrative where enlightened and awoken humans live in the real world that is a dystopia), The Matrix explores the notion of simulacra and reality.

Let us first look at the concept of reality in the history of Western philosophy. Plato believes that material things do not really exist. A table, for example, is merely a copy of or an iteration of the idea of table (table-ness). This is called idealism. Reality is merely in our perception. In Plato’s metaphysical cave allegory, humans are prisoners chained up in a cave facing a wall. Light comes from behind humans (from outside the cave). The shadows of “real” things are projected by this light onto the wall that humans look at. Humans take the shadow play for reality.

Zhuangzi, a classical Chinese Daoist philosopher of late 4th century BC, also has his allegory about reality as layered perceptions. One of the famous parables in his book, Zhuangzi, concerns a dream he supposedly had. In his lucid dream, he was a butterfly flitting through a field of flowers. When he awoke, he found that he was a man lying in his bed. Which one was reality and which one was a dream, he wondered? Was he a man dreaming he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he was a man? (Read the short story here.)

In 1981, French philosopher Jean Baudrillard wrote a philosophical treatise to examine the relationships between reality, symbols, and society. In Simulacra and Simulation, he argues that as society creates replicas of things, “simulation is no longer a referential being or a substance.” Artifacts and places (such as Disneyland) may initially be created as an imitation or parody of something, but over time the simulacra “substitute the signs of the real for the real,” replacing reality with its representation.

According to Baudrillard, there are four stages of simulacra, namely:

- Stage One: Copying the reality in a “reflection of a profound reality.”

- Stage Two: Masking the reality through perversion. The simulacra are clearly an inaccurate representation of reality and show that they are incapable of capturing the essence of the reality. However, since reality is obscured and cannot be independently verified, it is treated as maleficent.

- Stage Three: Concealing the absence of reality. The simulacra are copies of copies with no originals, though they claim to be a faithful copy. Arbitrary images are suggested as representations of things which they have no relationship to. Reality becomes increasingly hermetic.

- Stage Four: The Hyperreality. Pure Simulacra. The simulacrum has no relationship to any reality whatsoever. Signs merely reflect other signs. Claims to reality are based on other such claims rather than on substantive correlations.

In The Matrix, not only is the setting a simulated program to keep humans docile, but some individuals inside that program are also simulations themselves, or computer programs with specific functions, such as Agent Smith whose job is to hunt down rogue human minds.

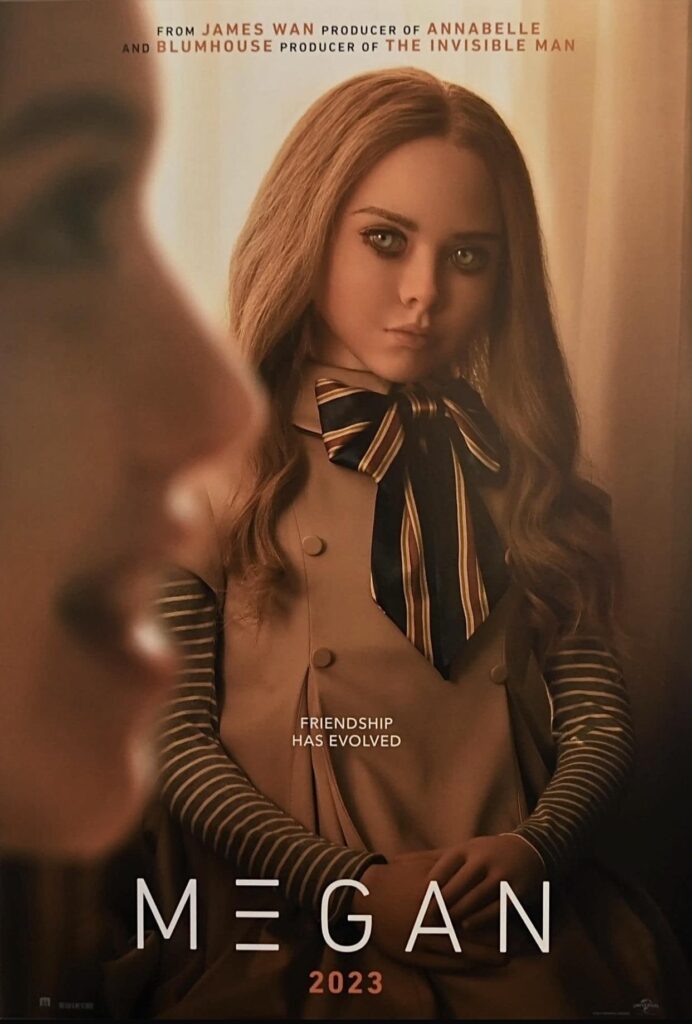

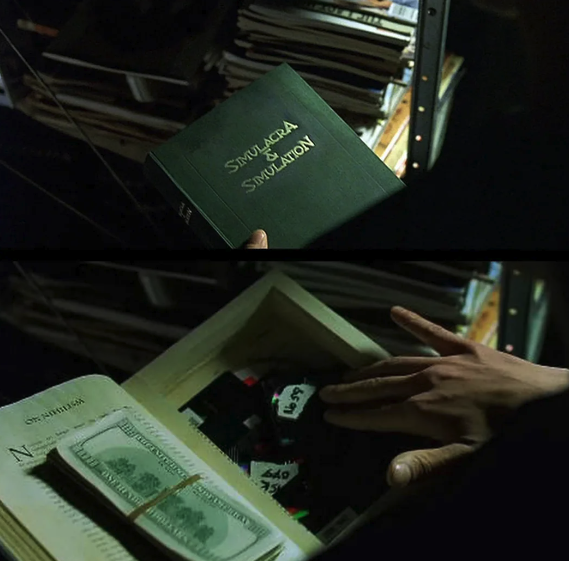

More interestingly, there is a scene in The Matrix where Baudrillard’s book, Simulacra and Simulation, makes an appearance. In the simulation where most human minds reside, which is called the matrix, Mr. Anderson is a cybercriminal and computer programmer (played by Keanu Reeves).

By day he works for a software company called Meta Cortex. By night, he is a hacker under the alias Neo (which is an anagram of the One).

In one scene, Mr Anderson is shown stashing illegal software inside a book, along with some cash. Money in the book echoes Baudrillard’s critique of capitalism as meaningless simulacra.

Note the golden font on the book cover and the black leather covers typically found on the Bible. Given that Mr Anderson will be awakened later and become the One, the savior of the simulated world, the religious connotation cannot be ignored.

A close-up shot reveals the book to be Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation. The book is opened to the chapter on nihilism. Nihilism is a form of skepticism about substance and meaning. Things in the world do not really exist (except in perception), according to nihilism.

Interesting, the fictional edition of Baudrillard’s book is itself a simulation of Simulacra and Simulation. The book’s core is cut out to accommodate more important artifacts. Perhaps Mr Anderson has finished reading the book. Maybe he does not regard the book as a useful companion on his journey to self-discovery.

A closer look reveals that half of the book is empty out to become a container for the contraband. Anderson puts his program on CDs and diskettes.

Books, of course, are technologies of representation and can be a type of simulacrum in terms of their representation of truth. The emptied out book symbolizes Mr Anderson’s disillusionment with the world he lives in. Click the image to enlarge it.

Conclusion

What do we learn from artificial bodies in popular culture? If one could create a replica of a loved one, what does that say about love and humanity?

Two interrelated concepts here are the artifice of identity practices and the invisibility of said artifice. The immediacy of cinematic language has a tendency to render itself imperceptible; film craft does not generally draw attention to itself as a narrative device. This cinematic invisibility, which results from self-effacing film conventions, has led to the invisibility of certain identities, particularly whiteness. Whiteness is framed as normative, hence unremarkable, through standardized White American accents as well as through its relative value to low-life characters.

Not all artificial bodies need repair, and not all robots need to become “real.” Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is an anti-transformation adaptation. In the film, Pinocchio does not actually become a “real” boy like his counterpart does in Carlo Collodi’s novel, because he has always been real all along.

What we see reflects how we see things.

Further Reading

Balsamo, Anne. “Forms of Technological Embodiment: Reading the Body in Contemporary Culture,” Body & Society 1.3-4 (1995): 215-237

Cave, Stephen, and Kanta Dihal, “Introduction,” Imagining AI: How the World Sees Intelligent Machines (Oxford University Press, 2023), pp. 3-15.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité October, 1984 (“Des Espace Autres,” March 1967 translated by Jay Miskowiec).

Hayles, N. Katherine, “Technosymbiosis Figuring (Out) Our Relations to AI,” Feminist AI (Oxford University Press, 2023), 1-18.

Joubin, Alexa Alice. “Anti-Asian Racist Misogyny in Science Fiction Films,” The American Mosaic: The Asian American Experience (Bloomsbury ABC-CLIO, 2022).

Kakoudaki, Despina. Anatomy of a Robot: Literature, Cinema, and the Cultural Work of Artificial People. Rutgers University Press, 2014.

Kreider, Tim. “A.I.: Artificial Intelligence,” Film Quarterly 56.2 (2002): 32–39.

Miyake, Youichiro. “The Potential of Eastern AI,” Ghost in the Shell, December 22, 2023.

Puar, Jaspir K. “I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess: Becoming-intersectional in assemblage theory. PhiloSOPHIA 2.1 (2012): pp. 49-66.

Tenen, Dennis. Literary Theory for Robots. W.W. Norton, 2024.

Tran, Jess and Elizabeth Patitsas, “The Computer as a Queer Object,” SoCArXiv, December 4, 2020.